A former student spread his conspiracy theory that birds aren’t real, and thousands are buying into it.

By Rachel Roberts

Feb. 9, 2019

The camera turns on. Brows are furrowed, posters are lifted and waved furiously, and pink hats bob up and down to the rhythm of the march. While political endorsements linger in the background, a tall, lean man approaches the scene equipped with his own political discourse: “birds aren’t real.”

These are not actors, and this is not a set. It is Jan. 17, the 2017 Women’s March in downtown Memphis, Tennessee. Peter McIndoe, a University of Arkansas student at the time, was in town to visit friends and decided to film a satirical video, featuring himself as the main character and a new controversy he created. “I’d always wanted to go to a rally and hold up a poster that had nothing to do with what the rally was about,” Peter explained. His goal of rallying people to support his pointless propaganda had come to life with a Sharpie marker and a poster that read, in all caps, “BIRDS AREN’T REAL” with a depiction of a bird and a slash through it.

Illustration by Ally Gibbons

Peter, an Arkansas native, invented the fake conspiracy Birds Aren’t Real, which pushes the idea that, since 2001, the U.S. government has replaced birds with drones that spy on Americans. Although the idea of birds being drones is hyperbolic, Peter’s mass audience does not seem to care. It’s a joke that thousands of people are in on — more than 70,000 people, that is.

While Peter enthralls his audience with enthusiasm and radical statements, such as the claim that birds are “Obama-drones” sent by “Killary Clinton,” he also serves his own creative aptitude by expressing his interpretation of America’s current political era.

After dropping out of the University of Arkansas, Peter made the move to Memphis to continue building the brand for the movement. The former student uses this platform to reveal political conversation swayed by radical beliefs. He highlights the extremities that society embraces as truth. He chooses to expose those behaviors of partisanship through a mock conspiracy.

Creating a Conspiracy Movement

After a day spent waving his controversy like a flag around the Women’s March, Peter had devised the parodic movement. The day of the march not only marks the birth of this conspiracy but also the day Peter’s friend group of seven came to be. The friends still refer to it as Bird’s Day, Peter’s girlfriend Madeline Houston said.

“We didn’t know the Women’s March was that day, so we just kind of stumbled upon it,” Madeline said.

At the top of a parking deck, where they saw the march begin, the friends grabbed a Sharpie and found a poster for a local theater production. Using a car hood as their workspace, they flipped the sign around to make a clean slate for their slogan and began designing their first Birds Aren’t Real artifact. When Peter arrived at the march with the poster in hand, many of the marchers were confused by his message, Madeline said, laughing.

While the group began protesting birds, a friend recorded a video of Peter in character as a radical conspiracist. Approaching other marchers and bystanders, Peter walked along the streets of Memphis asking people their thoughts on government surveillance and bird-drones. “Have you ever seen a bird in real life?” he asked one group of women. When they responded that they had, of course, seen real birds, he fired back his defense that Obama-drones have taken over.

“That day kind of changed all of our lives,” Madeline said.

“It was just a fun day, and then it blew up,” said Ray Schillawski, a friend of Peter’s and another witness to Bird’s Day.

Three months after the march, the joke was still relevant among the friend group. Peter created social media accounts for Birds Aren’t Real and began posting consistently to gain traction on the concept. After a few thousand followers picked up, there was a demand for merchandise to represent this newfound meme. Peter and Ray realized there was a business behind the joke, so they designed a logo for the brand and borrowed a vinyl cutter to make stickers. They soon has a stock of T-shirts and 20 stickers to sell.

Peter represents his brand by wearing a Birds Aren’t Real T-shirt. Photo courtesy of Peter McIndoe

“It’s kind of evolved into what it is,” Ray said. “I mean, 20 stickers isn’t a lot, but it was something to validate the idea, and we knew we didn’t have much time before it died out, so we needed to feed the flame.”

The Bird Brigade

Peter describes the “Birds Aren’t Real guy” as a parody of the average patriotic zealot. “The character itself is a satire of this radical partisanship that we’re experiencing every day,” he said.

Although viewers recognize him as this guy, Peter wants to keep his personal life detached from the role. He only refers to himself by his real name in one video. By not using his name in videos or posts, his identity remains anonymous to the viewers. Peter stays in character for the Birds Aren’t Real propaganda, even during interviews with news networks like the Houston Chronicle, to keep people questioning the truth.

“It’s a proof of concept for Peter,” Ray said. “It picks fun at everybody, but it doesn’t hurt anybody.”

University of Arkansas student Maylee Loften has been a follower and friend of Peter’s since the start of Birds Aren’t Real. “I remember Peter showing me the original video after he went to the Women’s March and being impressed with how funny and bizarre the movement was,” Loften said. “I remember getting my BAR sticker nearly two years ago from Peter and feeling so cool for knowing about this movement even though no one else did.”

The early supporters were steady and grew to 11,000 followers on Instagram within the first year. In September 2018, Peter and his team witnessed their biggest jump in following thus far. Peter attended a concert in Dallas where he reunited with one his favorite musical groups, Brockhampton, and its ring leader, Kevin Abstract. After the show, Peter found himself backstage hanging with the band members and discussing Birds Aren’t Real. Before he knew it, photos of Abstract sporting a Birds Aren’t Real T-shirt surfaced on the front page of Reddit. There was an influx of web traffic happening on his page from new followers, mentions and comments.

Whether due to his passion and zeal, or that people are beginning to believe his theory, Peter has brought in more than 70,000 followers on an Instagram page devoted to his campaigns — and a loyal following at that. He refers to patrons as patriots and calls them to “stay woke” as an army of truth-tellers, fighting the government’s lies about birds.

His interactions with supporters have become more frequent since the latest growth in viewership. Last fall, Peter and his girlfriend spotted a Bird’s Aren’t Real sticker on a girl’s laptop in a Memphis coffee shop. When he went over to introduce himself to the patriot, she was star struck. “She looked up, and it was literally like a girl meeting One Direction a few years ago,” Madeline said.

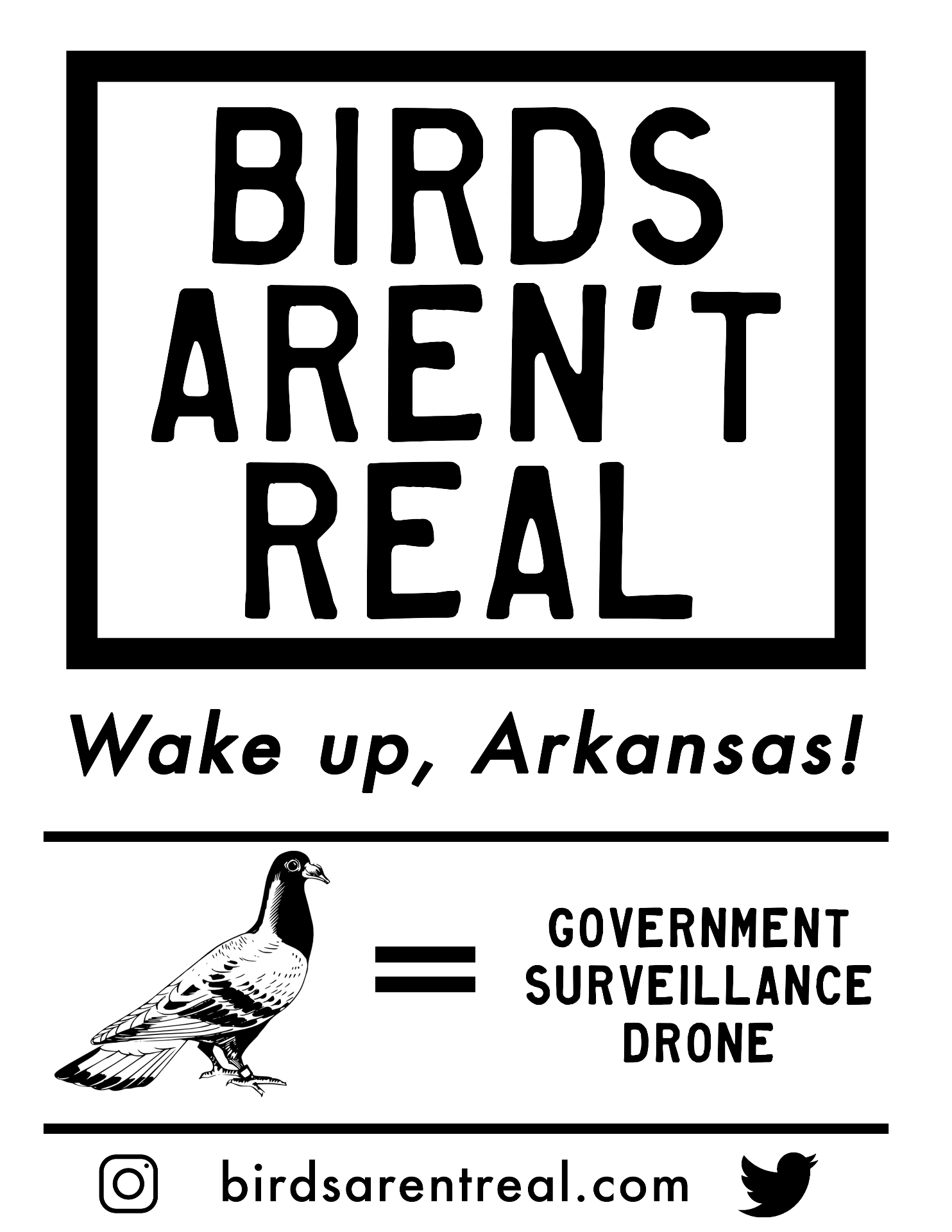

With new patriots joining the movement, Peter released print-off flyers on his Instagram page, leading people to distribute them around their cities, college campuses, social media, etc. The flyers themselves gained traction as people on Twitter and Reddit began reposting the advertisements. The two events altered the dynamic of Birds Aren’t Real, now that a mass audience was eyeing Peter’s work.

Peter and his team made a flyer for each state to spread their conspiracy theory.

Due to the influx of followers, the website sold out of merchandise, so Peter hired more team members to manage the business side of his movement. “I call it the ‘bird brigade,’” he said.

Risk and Reward

His internet virality and business success gave Peter reassurance in his decision to continue with Birds Aren’t Real, despite the pressure of those who doubted its future and affluence. “It was a bet I had to make,” Peter said.

“I could’ve been a psychology major or something,” Peter said, describing the way his life would have been if he hadn’t pursued this idea. He would probably still be a student at the University of Arkansas, but he wouldn’t have a platform for political satire. He took a risk that most people had warned him not to, and he moved to Memphis with a thousand white T-shirts and a fake conspiracy theory.

Birds Aren’t Real has become Peter’s full-time job, but he knows he can’t just talk about birds forever. He’s thought about turning the whole thing into a documentary. The film would break down the creation and psychology behind the prototype of a fake conspiracy and why Americans tune into ridiculous ideas like birds aren’t real.

Many people applaud him through comments and direct messages, assuming his feathered gospel mocks different political movements from feminism to Trump-ism. Others have contested his theory on birds and pose questions about bird meat and migration. Some even call him out for being crazy or absurd for believing that birds aren’t real. However, his movement is not about specific political ideologies, but instead, it is a reflection of American tendencies to believe fake news and radical ideas.

“It’s this branch of humor that’s very post-absurdist and sort of this weird alt-modern to where it doesn’t come out inadvertently insane, but it’s humor,” Peter said. “It’s about the ideology and this crazed era that we’re experiencing, and it seems so surreal. I’m trying to capture that same sense of surrealness in my videos by blending fiction and reality.”