Discovering my identity as the white descendant of Mexican-American immigrants

By Andrea Johnson

It shouldn’t have surprised me to see my grandfather cry at his brother’s funeral, but it did. My grandpa does not dwell on sentiments. He complains. He is stubborn. He doesn’t speak nostalgically about his upbringing as a poor, first-generation Mexican-American immigrant.

I hardly knew his brother.

My great uncle, Wensor Mena, used to visit my grandpa Bernard Mena at his home in Enid, Oklahoma, occasionally but not often enough for me to build a relationship with him. From outside the sanctuary, I watched Grandpa as he turned away from Wensor’s casket and hobbled toward the exit doors, arm in arm with my uncle, Tony Mena. As Grandpa walked, hunched over and barely reaching 5 feet 4 inches, Grandpa looked up at my brother and I waiting near the doors. His eyes were red from crying, and his brown skin, wrinkled like worn leather, was stained with tears.

Grandpa and his younger brother, Joe Mena, make up the last living children of Jesus and Maria Mena, two immigrants who crossed the Mexican-American border a century ago and raised their family in Enid. The Mena kids grew up and attended school in this small Southern town where maybe just four or five Hispanic families resided in the 1930s. Because of the color of his skin and his worn-down shoes, Grandpa stood out in the classroom, but he did not see himself as a first-generation immigrant who needed to assimilate to fit in. His parents had become naturalized citizens, and he grew up a citizen by birth.

“I never felt like I wasn’t an American,” he said.

It surprises people when I say I’m a quarter Mexican. My mother, Dana Mena-Johnson, appears Mexican because of her olive-toned brown skin, but my paler skin tells people I’m white. Both of my grandmothers had blonde or light brown hair, blue eyes and skin that burns at hardly a glimpse of exposure to sunlight. I never knew my dad’s father, but from the sepia-toned and out-of-focus photographs of the man who died too young, he appears just as light skinned.

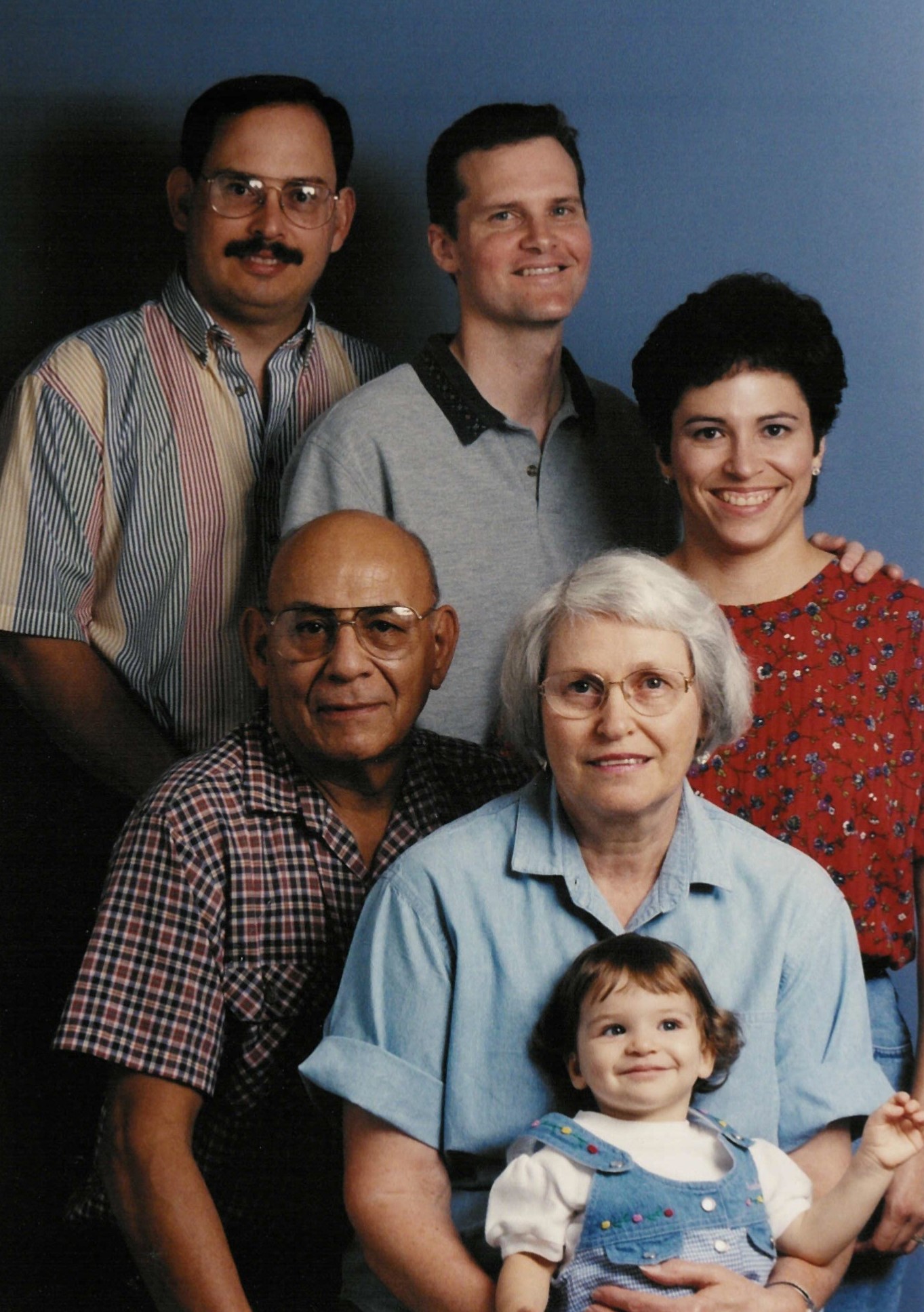

In 1998, the Mena-Johnson family joins for a photo. (back left to right) Tony Mena, Ron Johnson, Dana Mena-Johnson (front left to right) Bernard Mena, Nellie Mena, Andrea Johnson.

Filling out college applications required that I face the dreaded race and ethnicity question: How do you identify? Some of the applications allowed me to choose multiple identities, but others forced me to choose one, despite two of the options contradicting each other. It appeared I could be white or Hispanic, but not both. In these cases, I often chose Hispanic because it’s the only part of my ethnicity that I’m sure of, but I felt guilty every time. Am I Mexican enough to qualify as Hispanic?

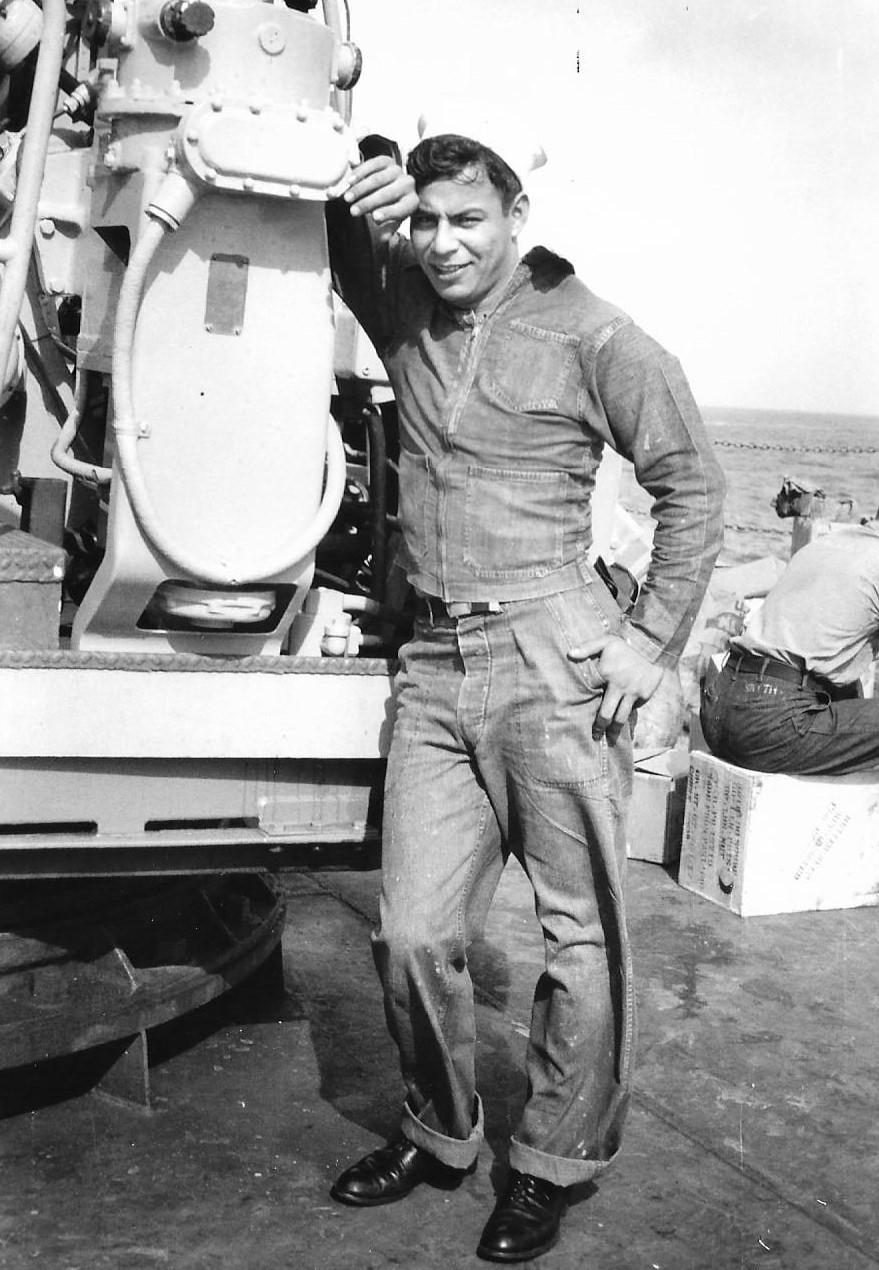

If asked about his ethnicity, my grandpa boasts that he’s an American-Mexican, not a Mexican-American, because the U.S. comes first with him. He owns a U.S. Navy hat that I remember him wearing around his house for hours one afternoon, proudly displaying the gift from a neighbor who recognized his military service. On a different day, he plopped an old photo album onto the kitchen table in front of me and asked me to point him out, noting that he was one of the darkest men in his division. I moved my finger over one of three non-white men, and he nodded. He shares few fond memories about his military experience, except that it “was as equal a place as any” in the 1950s.

He joined the Navy only to avoid being drafted into the Army. Obligation, not patriotism, became his reason for serving. But he boasts in his service because it makes him more than just an average U.S. citizen. It makes him a U.S. military veteran.

Bernard Mena served in the U.S. Navy, July 1952 through April 1955, working as a laundry machine mechanic aboard the USS Bayfield.

It took the heart-stopping text from my dad stating that Grandpa had fallen, hit his head and might not be okay for me to recognize the reality of the situation. Grandpa is the last living link connecting me to my great grandparents, but I know so little about them and my grandpa’s history.

It took me 20 years to ask my grandpa about his Mexican identity and childhood memories. It took me 20 years to search for answers as to how I could claim my own Mexican identity despite living a very American life. It took me 20 years to question how I ended up living a life of white privilege, while people who look like my grandfather still endure discrimination.

“Grandpa, I’m learning Spanish at school,” I told him one day, hoping he might engage in conversation about his childhood.

He acknowledged my statement but hardly looked away from the basketball game on TV. The conversation ended before it began, but days later he asked me whether I could count in Spanish. I told him yes, and he asked me to prove it.

“Good,” he smiled his approval. “I never could remember the numbers.”

The other Mena kids learned Spanish in school, but Grandpa didn’t get along well with the teacher. His parents reasoned that taking Spanish with her wasn’t worth worsening his reputation as the little Mexican troublemaker, so Grandpa never learned to read and write Spanish. He only learned from what his parents spoke, but his parents never encouraged speaking Spanish outside of their home.

“That’s just the way it was. My dad said, ‘If you live here, you speak the language,’” Grandpa said.

His father Jesus understood some English, but he didn’t learn to speak it like his wife Maria did. The language barrier hindered my mom’s relationship with Jesus, her grandfather, so she enrolled in a Spanish class during her ninth-grade year.

“I wasn’t very good at it,” she told me. “I couldn’t get the accent down, which everybody couldn’t believe because I was half Mexican.”

Her brother, my uncle Tony Mena, considered learning Spanish too, but learning English had been difficult enough because of his hearing disability, so he decided against fighting that battle again. Communicating with Jesus required translation help from my grandpa or Maria and occasional charade-like gestures, but Tony always understood when his grandfather called him “hijo,” or son. Jesus died in 1978 before Mom finished the class, and her Spanish studies did not continue after that.

After gathering as much family history as I could from the random memories Grandpa shared and the stories other family members told, I eventually decided to start from the beginning. I asked Grandpa where his parents were born; he smiled, shook his head and looked to his wife, a fair-skinned, witty German woman whose memories die each day from dementia.

“I don’t know,” he said with a chuckle.

Later that day, he handed me a stack of papers from an email he printed. Maybe I’d find answers in there, he suggested. My second cousin Lauren Shook, one of his brother Wensor’s granddaughters, had sent a chain of emails in May 2015 to share the genealogy work she started, which included birth and baptismal records. We connected, and Lauren helped fill in the holes in Grandpa’s story. In my story.

Grandpa had forgotten that his father, Jesus Jose Mena, was born in 1897 in Lagos de Moreno, a city in the Mexican state of Jalisco, to an unmarried woman named Melquiades Gonzales. Grandpa’s mother, Maria Gonzalez, was born in Salamanca, a city in the Mexican state of Guanajuato, in 1908. Jesus crossed the border through Laredo, Texas, in 1915, but Maria crossed separately at an unknown time and place. They met and married in Enid, Oklahoma, in 1923. Grandpa doesn’t know the reason they left Mexico – just that his father “left with the railroads,” seeking work from U.S. railroad companies. The railroads led him to Enid where he worked until retiring in 1962.

That seems to be the story spread throughout his family and corroborated by various documents, but Lauren dug deeper.

Maria and Jesus Mena raised five children, including my grandpa, Bernard Mena, in Enid, Oklahoma.

The Mexican Revolution began in 1910, and by the next year, Porfirio Diaz’s oppressive presidency had ended, sparking conflict and civil war in Jalisco. Between 1910 and 1920, the U.S. saw a spike in Mexican immigrants, and the number of Mexicans entering the U.S. more than doubled, from 221,900 to 486,400, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Many Mexicans fled war-torn areas like Jalisco during the civil war, and Lauren concluded that our great grandfather must have been part of this wave of refugees and immigrants.

Immigrant. Refugee. Both words have become so politically charged. And before looking into my family history, I never thought about how they fit into my story.

I asked Grandpa if he’d ever been treated differently because of this ethnicity.

“You’re talking about discrimination,” he half-asked, half-stated.

“Yes,” I responded. “Has anyone ever discriminated against you because you’re a Mexican?”

If people discriminated against him throughout life, he claims he didn’t pay it much attention. Lauren remembers hearing a story about someone throwing a brick through the window of his childhood home in an effort to scare the Mena family out of town. Grandpa did not recall this incident.

He remembers fighting kids in school, but he doesn’t remember exactly what they did or said that made him so angry. He remembers his mother marching to school with him to defend him in front of the teacher who threatened to paddle his behind. Maria knew that fair treatment came by demand, not by expectation.

“My mom said, ‘Well if you’re going to paddle him, you have to paddle the white boy too,’” Grandpa said, proudly recalling the day he escaped the paddle. “My mom wasn’t very big, but she was pretty fiery. She went to bat for us.”

Two generations later, my brother and I live a sheltered life, thanks to our white skin. Tony took after my grandmother and inherited paler skin too. He thinks that we inherited some protection – privilege, really – that some people might consider a blessing. After all, we haven’t faced outright discrimination.

Uncle Tony remembers suppressing his anger to keep from strangling the cashier who mistreated his father around 30 years ago. Standing in line in front of Tony, Grandpa appeared a lone shopper next to his taller, light-skinned son. The cashier looked past him.

“You’re next,” the cashier said to Uncle Tony.

“No, I’m not. He is,” he responded, looking toward Grandpa.

The cashier tried to ignore Grandpa again, but Uncle Tony refused to play along.

“It was just plain as daylight he didn’t want to deal with Dad,” he remembers, shaking his head.

Grandpa claims the situation didn’t bother him.

“Tony was just mad because he wouldn’t take care of me,” Grandpa recalled. “He said, ‘Dad, that guy passed you up,’ and I said, ‘I know, Tony. It didn’t bother me.’”

Mom exhibits a similar attitude to that of her father. Her classmates’ bewilderment at her lack of a Spanish accent never bothered her. Her appearance has caused confusion, but she won’t say that it’s caused her problems.

“If someone ever didn’t want to be around me because I was Hispanic, I didn’t know it,” she said. “I just assumed they didn’t like me. I didn’t blame things in my life on being Mexican. I’m still proud of my heritage, and I’m not going to hide it, but first of all, I’m an American.”

My grandpa, Bernard Mena, and my mother, Dana Mena-Johnson, stand together on her wedding day, Sept. 14, 1991.

Mom knows that Mexicans still face discrimination in the U.S. She, along with the rest of my family, know the stereotypes that depict Mexicans as lazy, mischievous and violent. Even the U.S. president enforces these stereotypes and rejects those who come from Mexico, a country he referred to as an enemy of the U.S. on Twitter in 2014.

“The Mexican legal system is corrupt, as is much of Mexico,” President Donald Trump tweeted in February 2015. “Pay me the money that is owed me now – and stop sending criminals over our border.”

“They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists,” Trump declared, kicking off his presidential campaign later that same year. “And some, I assume, are good people.”

Between July 1, 2015, and July 1, 2016, the Hispanic population in the U.S. grew by 1,131,766, making Hispanics 17.8 percent of the nation’s total population, according to a U.S. Census Bureau report. During that time, Trump cast blame on Mexicans for problems in the U.S. and proclaimed he would put an end to it with a wall between the two countries.

Mexican has become a sort of dirty word, said Xavier Medina Vidal, a first-generation Mexican-American immigrant and UA professor of Latino politics. But when we discussed my background, he encouraged me to embrace my white Hispanic identity. To him, this knowledge and pride of my family history and desire to maintain a connection with my heritage qualifies me as a Mexican-American.

“You’re Mexican. As far as I’m concerned, you’re Mexican,” he stated. “And what that means is that we as critical thinkers and responsible citizens need to deconstruct and demystify what it means to be Mexican or Mexican-American.”

I asked Lauren what she selects as her identity on paper and whether her research has changed her answer, but she struggles to determine where she fits in this puzzle too. Despite the label others might give her, she chooses to identify as Hispanic.

“When I got older, it felt like an important part of who I was, and a big part of that is because of how deeply I value my relationship with my grandpa,” she said.

When Wensor died, those who sat with him in his final hours describe his last words as jumbled, incoherent phrases. Grandpa suspects he was reciting The Lord’s Prayer in Spanish, which Jesus prayed every night before going to bed. He tried to teach Grandpa how to say it.

“I got those words tangled up … I can’t even remember them now,” Grandpa said.

He bowed his head and squeezed his eyes shut, but not for the sake of prayer. I watched him struggle to revive the memory.

“Padre nuestro, que está … estás en…” he began, but the next word wouldn’t come out.

“El cielo?” I said.

He looked up, slightly surprised but proud of my interruption, and smiling he simply said, “Yeah.”

His broken memories leave me with a disjointed family story, yet one complete enough for me to realize I’m not as distant from the immigrant population as I thought. My Mexican blood may seem watered down, but I’m still a Mexican nonetheless.

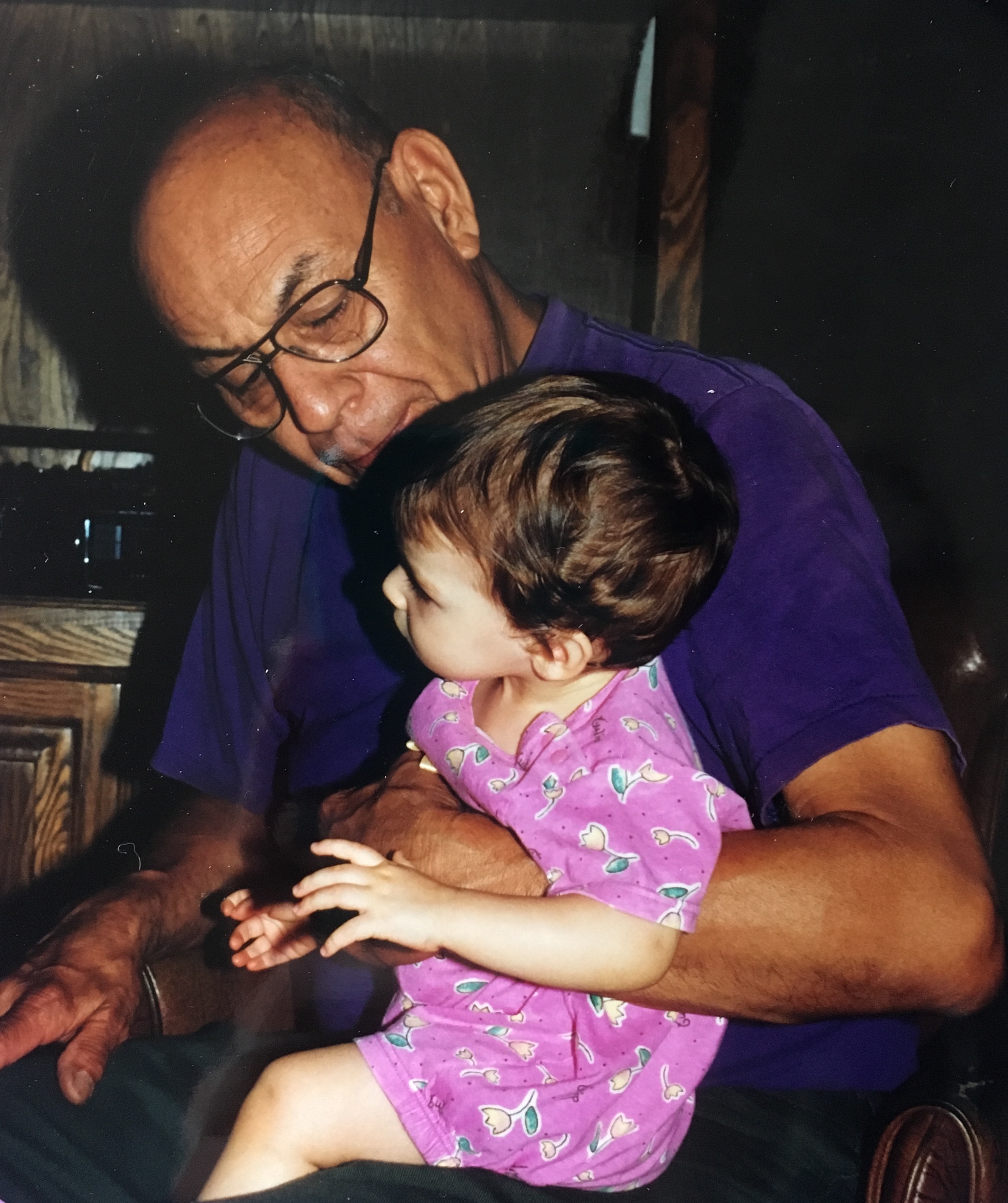

During a visit to Enid, Oklahoma, in July 1998, I sat on my grandpa’s lap to look outside the backyard window.

Andrea, wonderful article. We have only met at Wensor’s funeral but this makes me so proud of you and your family and OUR family! Well done! Tena

Hi Andrea, my name is Carmen Mena and I am Joe Mena’s granddaughter. I loved reading this because I relate to many of the experiences and feelings you share here. I have always felt so disconnected to the heritage I never learned about. My mom sent me this article and I really appreciate the work that you have done. Thanks!

Hi, My name is Gail and your mom was one of my best friends as a teen. We played softball together and my family often went camping with hers. I have fond memories of those days and Bernard and Nellie. I love your story!