A hidden journey from Islam to Christianity

By Elliott Wenzler

Comic by Olivia Fredricks

From the outside, he’s a man not so different from any other. He works in Northwest Arkansas; he raises his kids; he smokes the occasional cigarette; he loves his wife. He couldn’t live without her, he said. Despite working in a smaller kitchen than she’s used to, she’s still the best cook in the world.

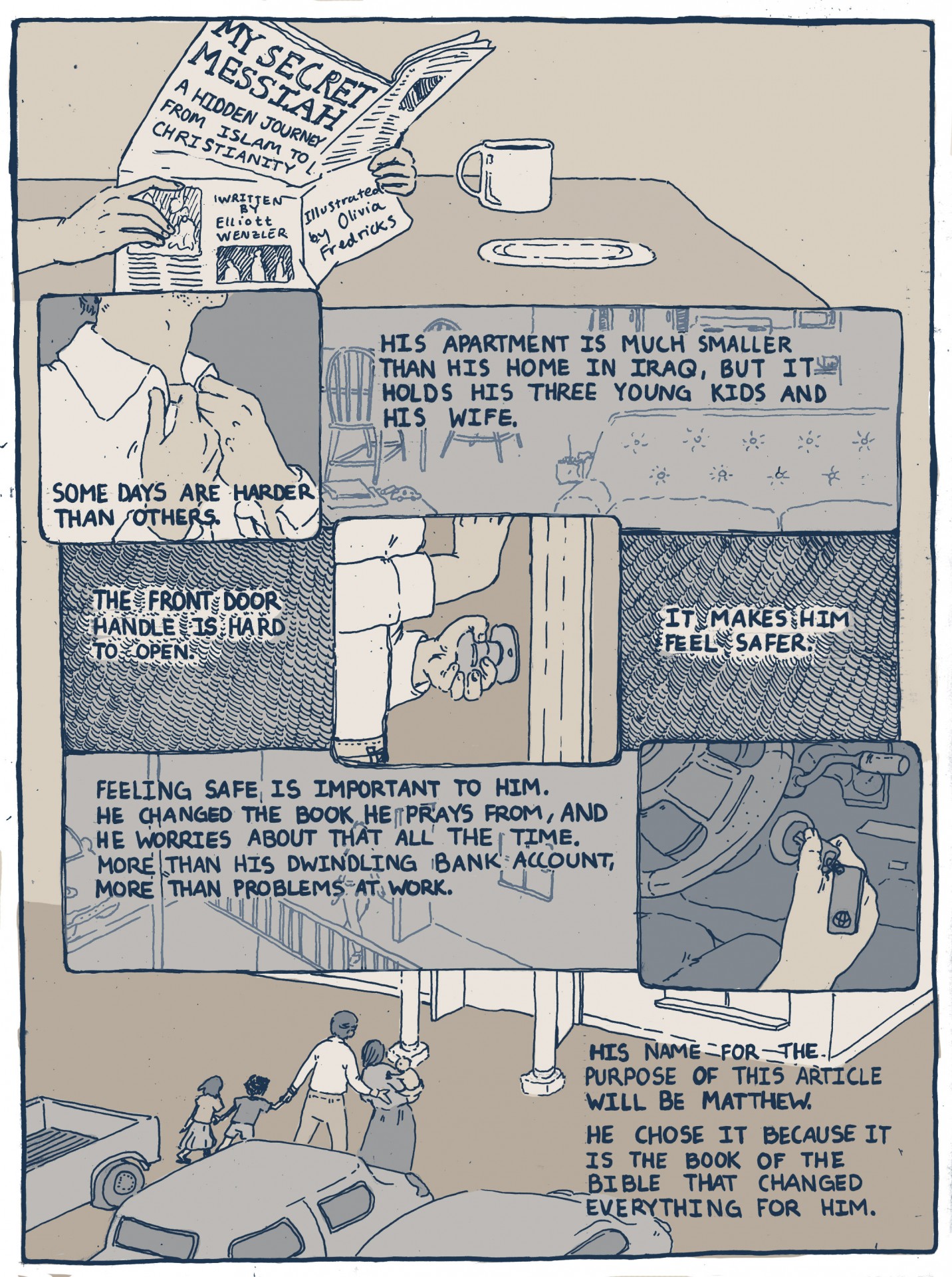

Some days are harder than others. Work goes long, and sometimes he doesn’t get to his apartment until around 6:30 p.m. The apartment isn’t extravagant: a long couch and a few small decorations on the walls. It’s nothing compared to what his house in his home country of Iraq was like. It holds his three young kids and his wife though. The front door handle is hard to open. It makes him feel safer.

Feeling safe is important to him. He changed the book he prays from, and now he feels like he has to worry all the time. He thinks and worries about it more than he checks his dwindling bank account, more than he stews over problems at work.

***

His name for the purpose of this article will be Matthew. He chose it because it is the book of the Bible that changed everything for him, especially chapter five.

Matthew’s identity will remain concealed in this article, protecting him as he opens up for the first time to someone outside his family or church about how he converted from Islam to Christianity.

Even though Iraq is over 6,000 miles away, Matthew will only discuss his true self and beliefs behind closed doors and in a low voice. He fears his Iraqi friends will find out and post about it on Facebook. His family might be punished, those in Iraq and the United States.

“You have no idea what’s going to happen if they know,” Matthew said. “Maybe I’m disowned from my parents. If I come back, I’m going to be killed for sure … I’m willing to give my life for Jesus Christ, but how about this kid?” He gestured to his 14-month-old son playing close by.

He talks about how his wife, who chose the name Marry for this article, posted something about loving America on her social media recently and soon received messages from fellow Iraqis questioning if she planned to change her religion. This kind of obsessive attentiveness is characteristic of the Iraqi community here, they said. The gossip is constant.

As he explains the details of the culture, he pulls his son into his lap. The toddler just grew his first tooth, and as he sits giggling in his father’s lap, he bites his father’s hand.

Matthew and his family aren’t alone in their struggle to convert from Islam; in fact, there is a group fighting to help people just like them.

Ex-Muslims of North America, an advocacy group founded in 2013, aims “to reduce discrimination faced by those who leave Islam, advocate for acceptance of religious dissent and promote secular values,” according to its mission statement.

EXMNA makes a point to distinguish between hateful racial bigotry and criticizing an ideology. An article was published on its website in 2015 with a title including “there’s a way to critique ideology behind religion without resorting to hate,” which urged readers not to follow President Donald Trump’s lead in policies like a ban people from predominantly Islamic countries.

Sarah Haider, co-founder of EXMNA, was born in Pakistan and raised in Texas as a Shiite Muslim. From a young age, she began reading the Quran critically and left the religion soon after her late teens. Now Haider does advocacy work to encourage the acceptance of religious dissent from Islam and works to create supportive communities for those who have left the religion, according to EXMNA’s site.

Haider is also passionate about women’s rights and civil liberties.

“Everybody that I was paying attention to was telling me that this was a wonderful humanist religion. But when I looked into it, it was clear that it wasn’t,” Haider said in an interview posted on the EXMNA site.

The group has communities in 18 cities across the U.S. and Canada, according to its website. They use the term ex-Muslim as opposed to something like atheist to show the added difficulties faced by Muslims who want to leave their faith.

“Most people who leave Islam tend to be isolated. They don’t talk to other people because they are concerned about the consequences,” EXMNA President Muhammad Syed said in an interview with The Thinking Atheist.

Pew Research Center reported in 2016 that 90 percent of the Middle Eastern-North African region criminalizes blasphemy, defined as speech or actions considered to be contemptuous of God or the divine, and 70 percent of the region criminalizes apostasy, which is the act of abandoning one’s faith.

Iraq, where Matthew is from, criminalizes both apostasy and blasphemy. The city he is from especially does not take deserting the faith lightly. That’s why he never openly considered it until he came to Northwest Arkansas.

“Tradition is more strict than Islam,” Matthew said, citing the fact that even Christian women in Iraq will wear a hijab because it is the cultural norm.

When Matthew came to the U.S., his dedication to Islam had already been fading for years. His uncle had been killed in the name of Islam, and he had started looking more critically at the Quran and other Muslim texts.

“I started to be atheist because I had seen many people killed in the name of Islam,” Matthew said. “I was just searching for the truth after ISIS took Iraq.”

He still was practicing Muslim prayers when he arrived, just like he had since he was a kid, but it didn’t feel right. He was losing his faith but still believed in God.

“I was just lost. I had no idea (if) I am Muslim or not,” he said.

Growing up, Matthew never considered Christianity because he learned a skewed version of the religion, he said. Matthew recalls learning that Christians believed that God and Mary had a physical relationship and that was how Jesus was born. It wasn’t until he confronted a Christian, asking how the person could believe this, that he learned it wasn’t truly a part of the faith.

When a Christian group came knocking on his door in Northwest Arkansas shortly after his family arrived, he was finally able to ask the questions he had always been curious about. When they told him the truth about their faith, they gave him a Bible as proof. That’s when he started reading it.

“I was shocked,” he said.

The story of Genesis was the same origin story that he learned in Islam, he said. He began reading the Bible daily.

One day, after living in Arkansas for a while, he asked his wife, “Do you accept me having four wives at the same time?” and after some hesitation and discomfort, she said no. Matthew was referring to a Quran law which allows men to have up to four wives. Her answer to the pivotal question set the family’s change in motion.

As Matthew recalls the beginning of it all, his 2-year-old giggles loudly in the background with a joy that is boundless and unfettered by the stress of such a question.

***

Experts agree that leaving Islam isn’t as easy as leaving other faiths.

“It is (more difficult to leave) in countries where religious law is enforced,” said Ted Swedenburg, a professor of Middle Eastern cultures at the University of Arkansas.

Religious law can be enforced by the state in places like Iran and Saudi Arabia and by individuals or militias in other Middle Eastern countries, which vary in the severity of measures taken.

“It’s not purely a religious issue,” Swedenburg said. There are also important political aspects for those who leave the faith.

One interpretation of Islam is that those who leave are heretics and should be punished by death, though there isn’t universal agreement on this among Muslims, he said.

For people in the Middle East, it is unlikely that someone who is no longer a believer would be open about it in public. The path of least resistance is to simply not observe Muslim practices but be quiet about it, Swedenburg said. There isn’t much room for atheists and definitely none for Christian or Jewish converts.

“When there are organizations around that are on the more extremist end, it’s not unthinkable that (this family) would be nervous about something like that, and they could somehow put their family at risk,” Swedenburg said. “But this would be militias, not the government.”

Armed militias have been present in Iraq since the days of Saddam Hussein. ISIS has only been in the country in the last five or so years. Although Iran and Saudi Arabia are the only Islamic States, or countries where government is primarily based on Islamic law, many others have laws influenced by the religion relating to divorce, marriage and inheritance, Swedenburg said.

“There are people who are working to bring more secular laws into being. In my opinion, that’s the step you have to take,” Swedenburg said. “Taking religion out of politics as much as possible and creating a society where one interpretation of religion is not the only one seems to be the way to go.”

Swedenburg worries that those who express dissent from Islam sensationalize and exaggerate points in a way that feeds into Islamophobia and is counterproductive. Some people who speak out against Islam after leaving the faith are using their experiences to make blanket statements, he said.

“Their word about Islam is taken as gospel truth,” Swedenburg said.

Swedenburg agrees that secular systems should be made that make it easier to leave the faith.

“I think you have to create political systems where there’s equality between faiths,” Swedenburg said.

***

When they arrive at church, Marry removes her hijab. She wears it in the grocery store and to meet with friends from Iraq, but she doesn’t need it here. At the Baptist church the family attends, about 10 miles outside of town, they are far enough away that it isn’t a concern that they might run into an Iraqi. Inside, they worship as they please.

Matthew and Marry sit close to one another as they listen to the pastor. They take each other’s hands after the pastor calls for a prayer on family. Matthew gently shakes his head and mutters with the intensity of his prayer.

They sit with the same couple that brought them to the church years ago. Matthew met the husband at work and after many questions about his faith began joining him at church events. A few years later, Matthew named his son after the friend who brought him to church.

The friend claims he didn’t really do much. Matthew was on his way toward the faith, and he just so happened to be there at the right time.

Matthew’s brow furrows as he ponders the pastor’s words. Occasionally, he does a quick translation in his phone. Usually he will check which verses will be read and prepare by reading the Arabic version beforehand.

There’s an unseen shroud over the sunny Sunday morning service. Earlier in the day, thousands of miles away in Egypt, two Christian churches were bombed in an ISIS-claimed attack, leaving the country in a state of emergency.

“All I can do is pray for them,” Matthew said about the incident.

He hopes to return to the Middle East someday. Matthew wants to share what he has learned with those he loves. He knows they haven’t heard the full story that he has now been exposed to.

Matthew talks a lot about the grace he has found in the U.S. He never felt any pressure to conform to the ways and religion of the South, but the kindness that he was met with in Arkansas spoke volumes.

“Here, they help anyone regardless of his religion or race – for that reason, I believe this country has grace,” Matthew said.

Swedenburg agrees that even with the growing Islamophobia in the U.S., it’s unlikely that the couple would feel the need to convert because of the surrounding faith.

People were never rude to Marry because of her hijab, and she didn’t experience any attempted proselytizing after arriving.

Even when they started attending church events, their pastor didn’t attempt to convert them until he was sure they had found their way on their own.

When their pastor Charles and his wife, Sophie, who declined to use their real names for Matthew and Marry’s anonymity, met them at a church bonfire in October 2015, they had already been praying for the couple, they said.

“We just didn’t want them to have an ugly American experience. We just wanted them to feel welcome,” Sophie said.

Matthew and Marry were both baptized in October 2016, one year after they met Charles and Sophie. Matthew came first in his acceptance, and Marry converted soon after. Pastor Charles wanted to be sure they were doing it for the right reasons, so he met with each of them individually to make sure they understood.

After these meetings he said he realized that Matthew and Marry were people who “on their own have each chosen to follow Christ,” Charles said.

***

When Matthew talks about his faith, his loyalty and love for his family and his work, he speaks confidently and without pause. The only thing that seems to make him skip a beat is questions about his future.

“I have no idea about the future,” Matthew said. “(I’m) asking for God to give me the plan for that.”

The program allowing him to live in the U.S. doesn’t last forever, but he hopes he can find asylum before that time runs out.

Someday, when his kids are old enough, he plans to show them the Quran. He wants them to read it and understand it for themselves. It would be nice to take them to his home country, but he doesn’t expect it will be possible for at least 30 or 40 more years.

His dream is to keep living here in Arkansas, the place he gets homesick for when he travels. He might not be able to make very much money, but it’s worth it to have safety and freedom.

“(The money) doesn’t mean anything,” Matthew said. “I’m going to live here with my religion even if I’m going to be poor.”

0 Comments