A family’s journey from the Congo to the United States

Story and photos by Andrea Johnson

May 20, 2018

John’s family expected he would follow suit and leave soon after they did. One month passed. Then two. Uncertainty set in, haunting him and his family members who were separated literally by oceans, but really, by words on paper. John’s family members, including his adoptive parents Watata and Safi Mwenda, landed in Arkansas on July 5, 2017, about one week after President Donald Trump’s 120-day halt on refugee admissions took effect. John would not see them again until he arrived on March 20, 2018.

John Feruzi (left) reunited with his family, including adoptive mother Safi Mwenda (right), in Fayetteville on March 20 after months of separation.

John still doesn’t know what went wrong with his paperwork, but whatever it was, it held him back at the camp long enough for the ban to take effect. The ban would allow a reassessment of the vetting process and strengthen security checks for those entering the country, according to White House press releases.

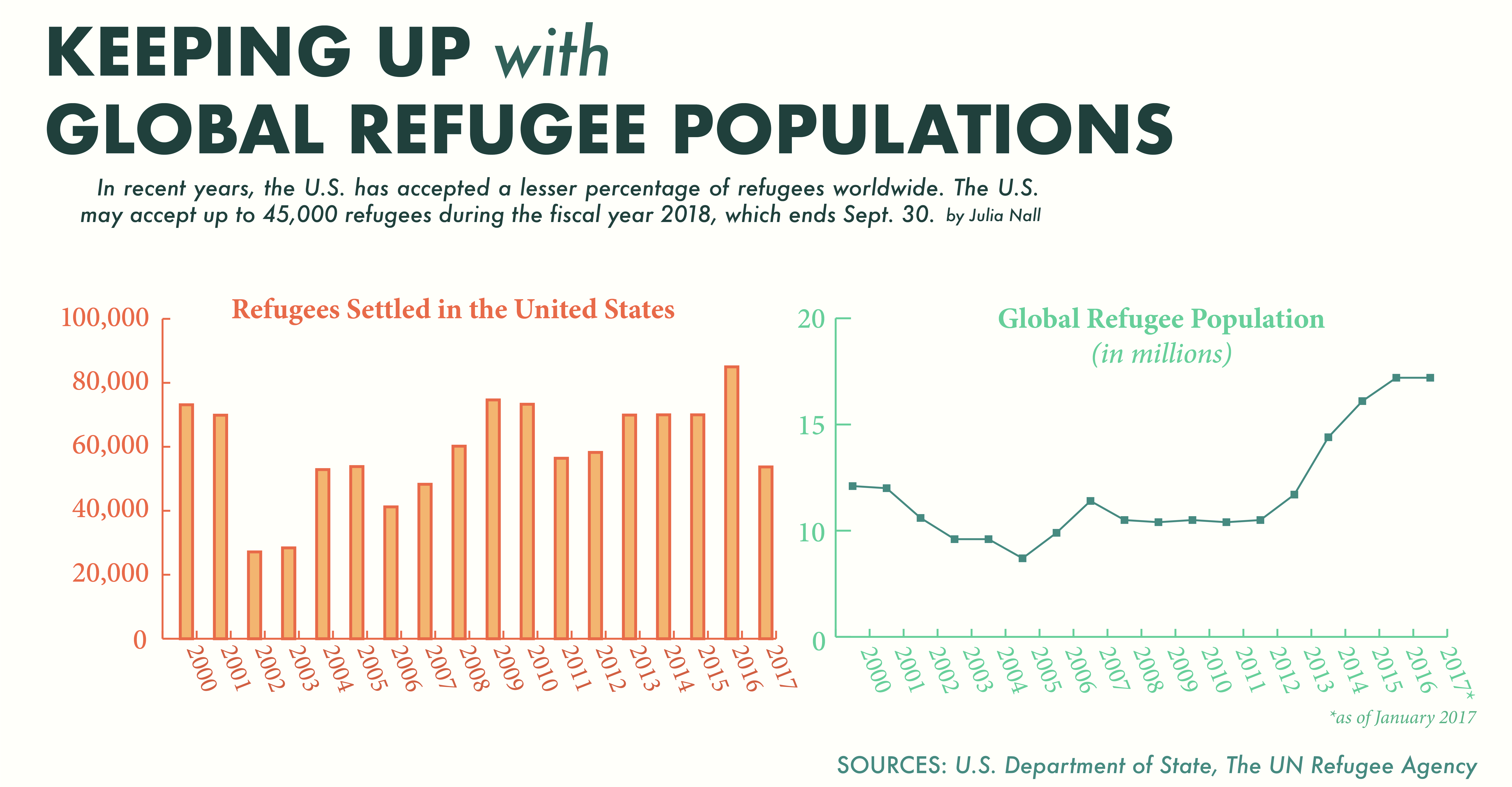

The Trump administration has placed a 45,000-person ceiling on refugee admissions for the fiscal year 2018, which ends Sept. 30. A White House press release justified the ceiling as being at “a level that upholds the safety of American people” by reducing potential terroristic threats. As of April 30, 12,188 refugees have been admitted for resettlement during fiscal year 2018, making up 27 percent of the quota, according to the Refugee Processing Center.

“We’ve never seen numbers this low intentionally. It’s pretty clear that this is on purpose,” said Nina Zelic, director of refugee services for the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, a national resettlement agency.

Under the Barack Obama administration, the U.S. accepted 69,933 refugees in fiscal year 2015 under a 70,000 ceiling and 84,994 in 2016 under a 85,000 ceiling, according to the Refugee Processing Center. Although refugee admissions increased from previous years, the U.S. still did not keep pace with the growing refugee population worldwide. Between 1982 and 2016, the U.S. resettled 0.6 percent of the total refugee population on average each year, according to a Pew Research Center analysis. But to continue resettling at that rate, the U.S. should have accepted more than 100,000 refugees in 2014 and onward. Obama proposed a 110,000 cap in fiscal year 2017 before leaving office, but the U.S. only accepted 53,716 under Trump.

Graphic by Julia Nall

Approximately 70 percent of legal immigrants follow a family member’s move to the U.S., according to a White House press release. Trump deemed the 2018 ceiling a more appropriate cap toward ending chain migration, or migration as a result of family connections. He claimed that admitting people based on family ties rather than merit-based criteria jeopardizes Americans’ safety and does not benefit the U.S. economy because immigrants’ skills might not meet modern economic needs. The press release cited a joint report from the Department of Justice and the Department of Homeland Security to state that roughly three in four people convicted of international terrorism-related charges since September 11, 2001, were foreign-born and entered the U.S. on the basis of family ties and extended-family chain migration.

Bill Schwab, a University of Arkansas sociology professor who studies immigration, thinks that recent political rhetoric regarding refugee resettlement and immigration often misleads people to see acceptance as harmful. Schwab is the author of “Right to DREAM: Immigration Reform and America’s Future.”

“Why don’t you use a different term?” he said to me when I asked why politicians speak negatively about chain migration. “I think a better term is family reunification. We’re not bringing fourth cousins over. We’re bringing over members of the immediate family. And when we look at refugees, this is extremely important.”

Most refugees do not want to leave their homes and struggle financially to do so, Schwab said. For some, it’s a matter of life or death. Choosing to stay could mean choosing to die. Watata explained his family’s life-threatening situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo to me through his one of his son’s translations.

“When sleeping in our home country, you always have fear that, ‘Maybe I cannot wake up tomorrow. Maybe they can kill me if it’s night,’” Watata said, describing the starkest difference between his former home and his home in Fayetteville, Arkansas. “But sleeping here, it is 100 percent true that I can wake up tomorrow.”

Watata, a tall man in his 60s, told me he led a relatively affluent life as a businessman in the Congo, and his status put his family of 13 people in danger. Six Mai Mai militiamen invaded his home in 2009, murdered his son and his son’s wife and kidnapped Watata. His wife Safi and surviving family members fled, assuming Watata had been killed as well. The men tortured Watata and left him on the side of a road where missionaries found him and took him to a hospital. He later reunited with his family.

The identities of the men who attacked his family remain unknown to Watata, but he thinks they were after his wealth. He decided their home was no longer safe and that they needed to leave immediately.

In all my interviews and conversations about refugee resettlement, the most common phrases I hear include, “the U.S. is a nation of immigrants” and “the U.S. is not doing its part to help those in need.” As a Lutheran pastor in Fayetteville, Clint Schnekloth’s reason to advocate for refugee resettlement stems from his faith. Sitting across from me in a cushioned coffeehouse chair, he explained this as he has many times before to those who have faith and to those who do not.

The Bible commands that Christians love one another, care for widows and orphans and stand up for the oppressed. Christians are comparable to refugees liberated by God. In Exodus 22 God issues the command, “Do not mistreat or oppress a foreigner, for you were foreigners in Egypt.” Clint can recite this verse and various others, but he knows that offering refuge to those in need is more than a Christian conviction. It’s a matter of people with the means to help, helping other people in need. He shares this message in church, on social media and in conversations with political representatives – even speaking to Sen. Tom Cotton (R) as a constituent at a crowded, animated town hall meeting last February.

“Refugees are getting unnecessarily politicized by some voices,” Clint told me. “We want to show that Christians are committed to compassion, and Americans are committed to providing refuge.”

This conversation was not foreign at Good Shepherd Lutheran Church, where Clint serves as head pastor. He had been involved in refugee resettlement efforts in Madison, Wisconsin, before moving to Arkansas in 2011, but it wasn’t until 2016, around the time of the Syrian refugee crisis, that the conversation came alive and spurred action in Northwest Arkansas. That year, 65.6 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide from persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations, according to a United Nations Refugee Agency report.

During spring 2016, Canopy NWA became the only nonprofit service partner in Arkansas under Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service. LIRS is one of nine resettlement agencies in the country. By December of that year, refugees had arrived to make Northwest Arkansas their home with help from Canopy NWA staff members, volunteers and co-sponsor families. Clint now serves as chairman of the Canopy NWA Board of Directors.

The federal government provides each refugee approximately $900, which a refugee resettlement organization manages, to start building their new lives in the U.S. The majority goes toward paying rent, said Lauren Snodgrass, Canopy NWA community outreach coordinator. Before a refugee arrives, Canopy NWA staff members find them an apartment where the landlord is willing to work with the staff. Some landlords refuse to enter into a lease agreement in which the tenant has yet to arrive and will arrive without a Social Security number and other forms of legal identification.

Canopy NWA helps refugees settle into their new lives by helping them obtain a Social Security number, offering job training and English classes and providing transportation until they get a driver’s license. Northwest Arkansas’ affordable cost of living, job availability and cultural diversity makes the area ideal for larger families like Watata’s, Snodgrass said.

Refugees with family members already in the U.S. tend to relocate with the resettlement organization that their family members connected with previously, leaving newer organizations like Canopy NWA open to accept those without a familial tie, said Zelic, refugee services director for LIRS. Many Congolese families, like Watata’s, most often enter the country without a location preference. LIRS officials place refugees in the community that can best support them by considering various aspects, such as medical conditions, languages spoken and ethnic background.

The University of Arkansas in Fayetteville has provided numerous resources for resettlement. Students work as Canopy NWA interns, and the majority of Canopy NWA translators who speak Swahili, Arabic and French come from the University of Arkansas. Snodgrass thinks that having a significant population of professors and international students with diverse backgrounds helps refugees better assimilate into American culture. Zelic also notes that the level of faith engagement and church involvement adds to the support refugees receive.

“A really welcoming environment has been critical for us in Arkansas,” Zelic said.

Canopy NWA has resettled more than 60 refugees since December 2016. LIRS officials originally told Canopy NWA to prepare for 100 during the 2018 fiscal year, but that number gradually decreased to 75 then 50. As of May 19, 17 refugees have resettled in Northwest Arkansas during this fiscal year.

“The fluctuation in Canopy’s numbers are the direct results of the president and the administration. And they are not following through with their commitment to resettle 45,000 refugees,” Zelic said. “It’s not typical to see a reduced number the way Canopy did, and we certainly know that Arkansas has the capacity, in terms of a welcoming community, to resettle more than 50.”

Watata’s story of escaping violence and bringing his family to a better life in Arkansas could be considered a success story for Canopy NWA. But what makes his family’s story so compelling for the organization and worth sharing is not the success but the separation his family is experiencing. A video shared on the Canopy NWA website and social media pages shows how Watata and Safi struggled to make sense of the separation from their son John.

The news that John would not be allowed to travel with the rest of the family came abruptly and with little explanation as the family left the refugee camp and approached the bus that would take them to the airport.

“‘John just can’t go,’ they said,” Watata recalled. “Well, I couldn’t argue with the officials, could I? … So I went to the airport.”

Safi cried as they left. Officials in Dzaleka later told John that he must wait longer because of the limit placed on U.S. refugee admissions.

“We cry about this. We really miss them,” Watata said.

John wasn’t the only family member left behind in the refugee camp. His sister Leticia still waits her turn along with her five children. Since Watata and Safi left with their own children, Leticia’s husband died from heart failure, and she gave birth to her fifth child.

Watata thanks the government who helped his family escape constant danger. He does not condemn Trump for anything that has happened to him or his family. But his face turns solemn when he thinks about Leticia and other refugees left behind.

The day I met Watata, March 15, he sat patiently in Northwest Arkansas Regional Airport, waiting to board a flight to Washington, D.C. At 5:30 a.m., the sun had not yet peeped above the horizon, allowing a shade of light blue to overtake the dark night sky for another couple of hours. Watata wore dress slacks, a striped button-up shirt and shiny black shoes with bright orange socks, an ensemble that might gain favorable attention from the politicians he planned to confront later that day. He would join a group of Canopy NWA staff and volunteers – a businessman, a pastor, a mother and son, college students – who would meet with Arkansas representatives to discuss the importance of resettling refugees in the U.S. and keeping families together.

Talking face-to-face with these politicians might bring Leticia home sooner and allow more refugees like himself to escape suffering, he reasoned.

“They’re suffering at this very moment,” Watata said to another reporter who interviewed him in the airport.

Emily Crane Linn, executive director of Canopy NWA, translates for Watata Mwenda while he speaks with KNWA-TV reporter Deni Kamper on March 15.

Watata had shared his story of separation with anyone who would listen, hoping that publicity would lead to his John and Leticia’s homecoming. But this story was changing even as we spoke in the airport. Watata knew that John was on his way to the U.S. and would land in Arkansas just a few days after Watata returned from D.C. His matter-of-fact demeanor changed when I asked him about the hopeful news.

“Right now, my biggest joy is that I get to welcome my son John back home,” Watata said, his cheekbones forming a sharp, square angle that remained as he smiled.

In D.C., Watata shared his story with Arkansas representatives but focused on Leticia and those left in limbo, and Canopy NWA staff and volunteers offered their perspectives on refugee resettlement efforts too. They met with Sen. John Boozman (R); Edward Linczer, Cotton’s staff person for immigration issues; and a staff member from Rep. Steve Womack’s office.

Javier Cuebas, LIRS directory for advocacy, has observed that the loudest voices or most persistent advocates tend to influence busy state representatives most, even if those voices are few, he said.

“Canopy has been a trailblazer in paving the way for more groups at the state level to actually come to Washington, D.C., and express the local voices, which is probably the key to success in the current environment,” Cuebas said.

Snodgrass thinks that Boozman is starting to soften up and openly support Canopy NWA’s mission, but Cotton and Womack continue to make excuses based on safety concerns. Canopy NWA staff and volunteers asked that Boozman meet with Womack and write a letter together in support of bringing in more refugees. They asked that they hold Trump accountable about bringing in up to 45,000 refugees. In public statements, politicians speak more often about refugees as part of a larger problem. In person, these representatives seemed more supportive of the individual people in need, Snodgrass said.

“Arkansas is a good place for living,” Watata told Arkansas representatives in D.C. “Help bring the people in trouble around the world to Arkansas.”

Almost nine months after Trump’s refugee ban began, John reunited with his family in the U.S. on March 20. He walked the final stretch of distance between him and his family members waiting beyond the airport terminal in Northwest Arkansas and approached a group of smiling people, some he knew and some he didn’t. Watata held a sign reading, “WELCOME HOME, JOHN FERUZI,” in chunky block letters filled in with red, white and blue.

When John reunited with his family, celebrations ensued. His adoptive mother Safi embraced him, lifted him off the ground and shook him. His brothers and sisters joked and laughed with him, and they took photos with each other and with the others who had joined to witness the arrival.

Watata calls the Democratic Republic of Congo his home country, but he laughs at the thought of returning. Arkansas is his home now.

Watata and Safi live in a small apartment close enough to the interstate to hear wheels speeding rhythmically across the freshly-paved asphalt. His sons live nearby. It only takes about 10 minutes for John to get there.

A doormat outside of Watata and Safi Mwenda’s home marks their happy place.

Safi answered the door the morning I stopped by. I told her I had spoken with John and he gave me her address as a meeting place. She stared blankly and let me carry on for a while before responding in Swahili, a language I cannot understand, yet she did not turn me away. She welcomed me into her home. She welcomed a stranger who asked for help. The irony did not escape me.

Inside, brown leather couches separated the living room from the dining area from the kitchen. Safi washed dishes and trimmed chicken with the overhead light turned off, satisfied to work with only the overcast sunlight streaming in across the room. They did not have electricity in their Congolese village.

A family photo taken in the airport hung on the wall across from an empty dining table with seven chairs crowded around it. His family members living in Fayetteville could fill this table and would even need a few more chairs to seat everyone. But a full table in his new American home cannot completely satisfy Watata so long as Leticia is not there.

The pain of leaving someone behind feels like a heavy weight constantly bearing down on him, he said. It’s a lingering thought in his mind that reminds him someone is missing. When Leticia arrives, he “will be happy forever.” Watata and his family members worry more about Leticia and her children now that John is no longer with her in the refugee camp.

“We have to get them here,” said Jules Mwenda, one of Watata’s sons. “She still has small kids, so we don’t know what kind of life that is getting there. She is alone now.”

Each time I spoke with a member of their family, they reminded me that, although they feel grateful for a new home, they ache for Leticia. Safi still cries for her, John said.

When I asked John what about Fayetteville stands out to him, I expected he might point out some cultural aspect that differs from the Congo. His answer reminded me how blinding American privilege can be.

“There are people living their lives in peace (in Fayetteville),” John said. “If you think to go somewhere, you go without any problem – free. You always have peace.”

It was simple: Living in Fayetteville provides John and his family the safety and hope his former home could not.