How taking self defense classes is making me a stronger independent woman

By Andrea Johnson

Feb. 28, 2019

I saw him in my rearview mirror. It was dark but not late. He approached my parked car wearing a thick coat, hood up. One arm was crossed over his body, obstructing a hand from view inside the coat. Did he have a gun? A knife? I shifted gears into reverse without thinking twice, sweeping out of the parking spot just before he got close enough to block me. I looked back as I left the parking lot, and he was watching my car. Then he walked the other direction, away from my former parking spot, turning his head from side to side.

Nothing happened to me. And maybe nothing would have happened to me. Maybe, because I’ve been taught to watch my surroundings and be skeptical of men when I’m alone, I just misinterpreted his movements. The temperatures had dropped, requiring any sane person to bundle up. Maybe he was walking to his car too.

But the lot was nearly empty. It was closing time at the Fort Smith Public Library on a Saturday night. Not many people go to the library at 5 p.m. on a Saturday. I was there alone, passing the time before I had to be elsewhere. I walked to my car relaxed, not expecting someone might be watching me. I never saw where he came from, and he appeared in a way that made me shiver as I drove away.

I’m a 5’2’’ and 115-pound woman, and for years I made excuses for how I could overcome these facts and defend myself. I’ll just poke my keys through my fingers, giving my tiny fist a more effective punch. When I’m walking alone, I’ll discourage any nearby attackers by holding my phone to my ear and pretending to tell my imaginary friend on the other end that I’m coming to meet them – just give me five minutes and I’ll be there. I’ll scream. I’ll kick them in the nuts. I’ll jab their eyes out. And I’m in good shape! I mean, you won’t see any CrossFit biceps through my Forever 21 sweaters, but I can run a mile. I can’t really outrun anyone with longer legs than me nor can I overpower most able-bodied men, but I had convinced myself I could improvise with what I knew.

After a month of Krav Maga self-defense training, all those tactics sound pathetic. The jolt I felt from the instructor’s practice grab was enough to shake me into realizing I’m not ready to face a real attacker. There are too many ways for someone to attack and cause life-threatening harm to me in seconds. If that hooded figure had emerged from the shadows a minute earlier with malintentions, I doubt a minor cut from my house key would’ve saved my life.

Being alone, especially in a secluded place, makes anyone vulnerable to an attack, said Sgt. Anthony Murphy, a Fayetteville Police Department officer. Being in public doesn’t guarantee safety though. Attacks often happen in parking lots and other routinely visited areas.

The 2017 violent crime victim rate in the U.S. was about 21 per 1,000 people ages 12 and older, up from 18.6 in 2015, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics’ most recent report. Violent crime includes robbery, assault, domestic violence and rape. The rate of male victims increased by about 28 percent to 20.4 per 1,000 people, closing the gap between the male and female victim rates.

I’m not a fighter. I finally admitted that, as if it weren’t already obvious. I signed up for self-defense training and decided to become a fighter. Or more so, I decided to arm myself with the mindset of a fighter. It’s humbling and yet simultaneously liberating.

…

People often sign up for self-defense training with fear as their core motivator, said Cole Saugey, a Fayetteville Krav Maga instructor. Sometimes it’s a traumatic experience that pushes someone to prepare for future threats, but other times, it’s simply the realization that the world is dangerous and people are cruel.

“The worse the world gets, the more people come to us,” Saugey said.

Since October 2018, female membership at Fayetteville Krav Maga has grown by about 10 women as of Feb. 26, Saugey said. Overall membership has grown by at least 25 percent. Some cited the abduction rumors involving the University of Arkansas campus and an unreported incident at the Northwest Arkansas Mall as their reason for joining.

I’ve been telling myself for years that I need to sign up for a self-defense class. I’ve seen a few YouTube videos about self defense and attended an hour-long demonstration on campus, but I knew that wasn’t enough preparation for a worst-case scenario. I wouldn’t remember what I saw. I needed to practice and teach my body to react under stress.

My search for recurring classes in Fayetteville that focus primarily on self defense didn’t yield many options. Some local martial arts gyms offer classes. For example, Fayetteville Martial Arts on Township Street hosts a FAST Defense seminar, but it’s a three-hour, $45 class that occurs just twice a year in January and July. The Fayetteville Police Department has offered self-defense classes in the past, but in the last couple years, officers have only scheduled classes with specific groups that request one, Murphy said.

I remembered seeing news about a Krav Maga self-defense class at the UofA, so I emailed Ed Mink, who organizes the program within the UA Pat Walker Health Center, for more information. When he replied, I signed up immediately and paid the student price of $40 for eight weekly sessions. No more procrastinating. The class, which Saugey teaches, began Jan. 15 in the health center.

Krav Maga is a form of self-defense training developed by the Israeli Defense Forces that emphasizes survival strategies, meaning you train as if preparing for a life-or-death matchup. You neglect technique and rules that exist in organized fighting. If someone attacks you in a parking lot or on the street, they won’t play by any rules. Therefore, you can’t fight back hesitantly. You fight aggressively to survive.

Illustration by Ally Gibbons

“We’re a lot more vulnerable than we realize,” Saugey said. “You always have to assume the worst.”

That’s what I learned on day one.

…

On Jan. 15, I stood in a circle with strangers like me – people willing to learn how to protect themselves. The majority were female students, but throughout the next month, more men would join the class and make that demographic more even.

The way Saugey described his class on the first day put me at ease. The violent nature of Krav Maga made me nervous, and I worried I could never overcome my physical traits that make me an easy target. But Saugey said that sometimes violence is necessary to make up for physical shortcomings; violence is an equalizer. And the point of Krav Maga training isn’t necessarily to win a fight – not if you define winning as fighting until someone falls incapacitated.

“The biggest thing I have to convince people of is that they don’t need to focus on how to fight,” Saugey later told me. “They need to focus on how to escape. That’s the biggest misconception. People think they want to be in that fight, and people don’t realize that they really don’t.”

Even a person with training could find themselves facing an attacker with a dangerous, unfair advantage like a weapon or a partner. He stated that his goal for us is to learn ways to quickly and effectively react to the most common situations and develop muscle memory.

Hardly anyone spoke to each other during that first class. We listened to Saugey’s instruction and watched him demonstrate basic palm-heel strikes, then we struck the air for practice, hands held in front of our faces. Next, we added a kick to the groin – a signature Krav Maga move – into our sequence. Saugey explained that palms work better than fists because palms can absorb more impact without damaging the hand or wrist. He demonstrated how a fight like this might play out by asking Mink, who helped organize the class and assists in teaching, to act as his attacker. We practiced hitting and kicking Saugey while he held a thick pad.

Later, we formed two lines facing each other from across the room. Saugey dropped a rectangular black pad in front of each person at the beginning of the lines and instructed them to put it between their knees on the ground.

“This is where most fights end up,” he said. “And it’s where most sexual assaults happen.”

I realized the shape and size of the pad slightly resembled a man’s chest and torso. I bit the inside of my cheek – a nervous habit of mine. I didn’t want to imagine this scenario.

Saugey thought we should feel what it’s like to strike someone on the ground for 30 seconds before we discussed certain scenarios. Because there were only two pads available, the rest of the class could only watch while waiting their turn.

It felt like a performance. I hit the pad, swinging elbows and hands at the ground as Saugey had demonstrated. I felt weak. When the man across from me hit his pad, the impact made a smacking noise like hail on a rooftop. My impacts sounded like gentle rainfall. The bag doesn’t even fight back, yet I felt like it won.

“Time,” Saugey said, looking at his stopwatch.

My face felt hot as I slid the pad to the woman on my left and stood up, hair dangling in my face because it fell loose from my ponytail.

“Nice,” one woman said to me from across the room, smiling in quiet support.

“Thanks,” I said back, laughing a little.

…

“There’s a lot of women who need to get in it but don’t have that confidence even to start,” said Tammy Roeder, instructor of a women-only Krav Maga class. Saugey thinks men often overestimate their ability to fight, whereas women tend to underestimate themselves.

Tammy Roeder, Fayetteville Krav Maga instructor, trains with Fayetteville resident Kate Knox on Feb. 18. Photo by Andrea Johnson

In August, Fayetteville Krav Maga started offering a women-only class to provide a safe space for women to ease into training. It started with about 12 women and has grown to classes of up to 25, Roeder said. Roeder focuses on building confidence, encouraging situational awareness and preparing for scenarios more common with women. They talk about how to protect themselves from sexual assault and attacks involving hair pulls, and then they practice those defense movements.

“Some women have been through things, and they don’t want to put themselves out there yet in that situation with men,” Tammy said. “They’re looking for a way to feel comfortable – feel safe.”

The women’s class is somewhat of a support group, but eventually, Roeder hopes her female students will feel comfortable training in a co-ed environment. Because attackers are often men, she thinks that training with men helps bridge the gap between what’s comfortable to practice and reality.

…

Kate Knox, a Fayetteville resident, still doesn’t like hugs from behind, even from her own husband, she said. It feels too similar to how a man attacked her in her home 10 years ago.

She was a UofA student at the time, in 2009, and had recently gone through a divorce. It wasn’t a good time in her life, but that night was supposed to be a good night. She went out with friends to George’s Majestic Lounge, and they came over to her place afterward with a few guys they had met. As the night faded away, her friends left, and a couple of those guys fell asleep on her couch. It wasn’t a big deal, she reasoned. She’d ask them to leave soon enough.

Assuming both men were as intoxicated and sleepy as they appeared, Kate turned her back on them to go to the bathroom. One followed without her knowing. Next to the bathroom inside her room, he shoved her forcefully from behind, and she doubled over, gasping for air as she leaned over the bed. He yanked her hair and forced her onto the bed as she reached desperately for anything that might help her. She felt frozen, unable to stop him from controlling her – from raping her.

The nightmare lasted for years.

“For years, I could smell his aftershave and I could feel his beard,” she said, reflecting on the attack. The trauma evolved into rage. She felt angry. SO angry. She saw a therapist regularly for a year after the attack. Five years later, she started seeing a different therapist for another two years.

In August 2017, Kate’s mother introduced her to Krav Maga, and it became an outlet for her anger, Kate said. Little by little, she gained strength, lost weight and discovered a newfound pride and confidence in her abilities.

“Over time, I got to learn how to kick ass and started feeling pretty kickass,” she said. “It’s so empowering.”

Knox practices defending herself against a knife attack with Roeder at Fayetteville Krav Maga gym Feb. 18. Photo by Andrea Johnson

She has friends who have experienced similar assaults and has heard them tell their stories somewhat shamefully. She understands how it feels to blame yourself for being in the situation or reacting a certain way. To those who feel ashamed, she says “it’s okay if you froze.” For her, Krav Maga offered redemption.

“Something was taken from you, and this is one way to get it back,” she said. “It might not be the same. (You) might be stronger than before. But definitely some part of you comes back.”

Kate regularly attends classes at the Fayetteville Krav Maga gym. She dreads practicing hair-pull attacks because of the memory it revives, but reliving her past isn’t stopping her from protecting her future.

…

Each class, Saugey reviews what we learned in past classes, demonstrates a new sequence of self-defense movements and gives alternatives for certain deadly strikes, like a “hammer blow” to the back of the neck.

“Your life, your choice,” he’ll say.

We run through the sequences with our partners – grabbing wrists, pretending to choke each other and faking a bear-hug attack from behind – and stop just short of making contact with any strikes. In my class of about 10 people, I’ve grown accustomed to partnering with a female student who is my size – the same woman who boosted my confidence the first day. She moves gently and respectfully, and although I’m thankful to have made a friend who I feel safe with, I question whether I’m truly preparing myself for a real attack.

Sure, I know what to do now, and I’ve developed some muscle memory. But I haven’t been physically challenged yet. I still don’t know how I’d react under stress. I hesitate to say I want to know, but I do want to prepare myself just in case.

The class at the UofA is a beginner’s class usually made up of students and faculty with little-to-no training, Saugey said. The class I’m enrolled in ends March 5, and the next one begins March 12. You can register and pay at the Pat Walker Health Center, and I suggest recruiting a trusted friend to act as your loyal attacker. Saugey will also teach a free seminar 6:30-8 p.m. March 5 in room 220 of the Health, Physical Education and Recreation Building.

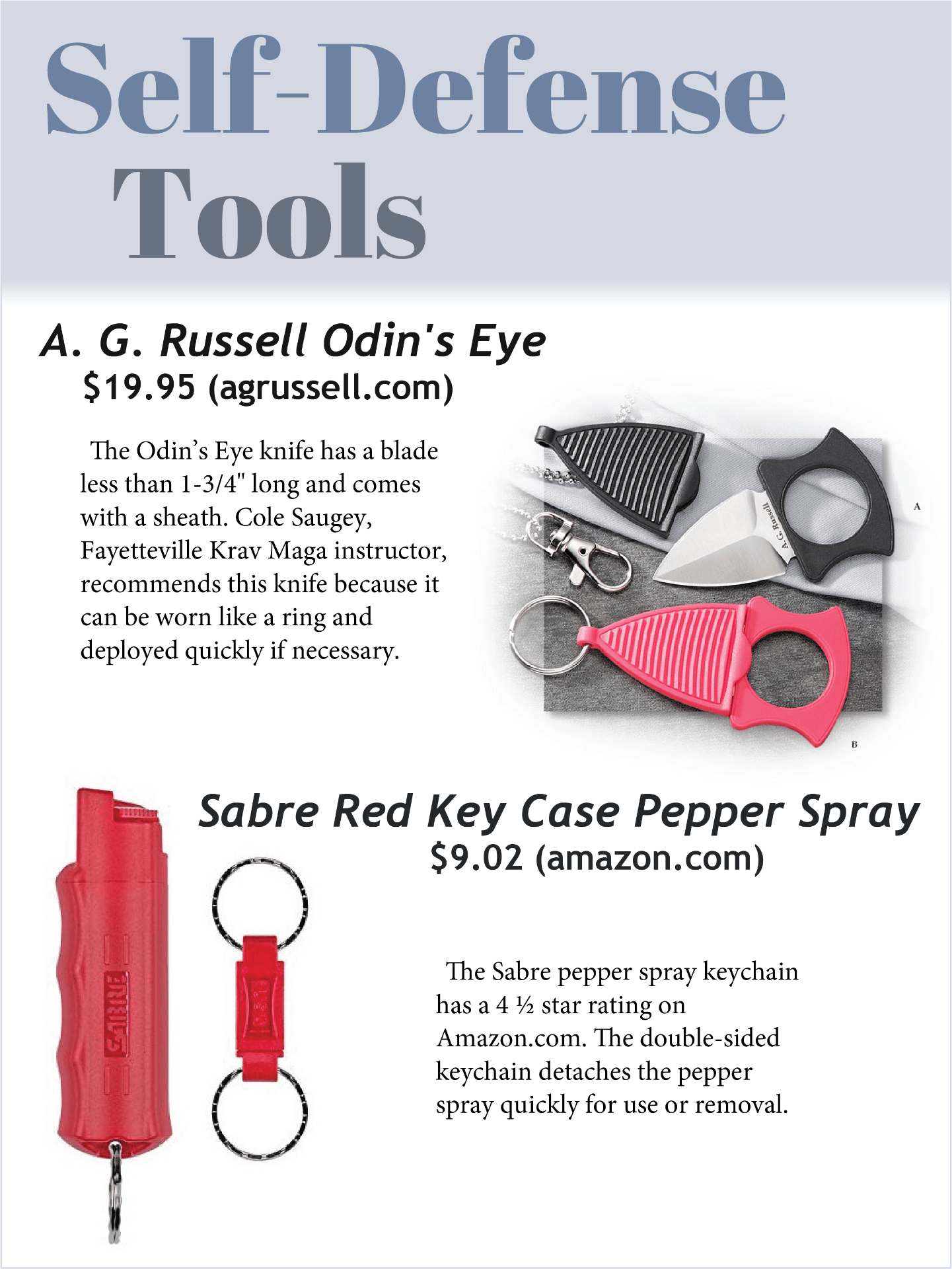

These weapons fit safely onto a key ring and are allowed on campus for self-defense purposes only. Graphic by Julia Nall

The classes at the Fayetteville Krav Maga gym offer training for all levels each weekday, and the instructors there are more likely to challenge students who have trained for a while, Saugey said. If I want to, I could sign up and experience a practice scenario more like a real attack to gauge how I might actually react. I could hit and kick someone in padding without worrying about injuring a friend. So I’m signing up for more, because I think that’s what I need.

After I graduate and get married in May, I will likely move to a larger, more dangerous city than Fayetteville, and I don’t plan on hiding at home. I’ll have a husband, but I can’t rely on him to protect me wherever I go. I enjoy being an independent woman. I will go to work by myself, shop and run errands by myself and maybe stay out late working in coffee shops by myself.

I will always believe in the buddy system. I believe that, if it’s an option, it’s better to humble yourself and ask a man you trust to walk with you rather than walking alone. I believe in pepper spray and other keychain weapons. And I still believe in kicking any male attacker in the nuts and poking his eyes out.

I also believe that being an independent woman in 2019 can be dangerous, so it’s worth taking action to equip myself for the role. I pray I never have to use what I’ve learned in training, but if the situation arose, I know I’m better off than before.

Krav Maga is for young AND OLD, male or female. This is a much needed article and is WELL DONE. Thank you for addressing this topic.