Despite hashtags and marches, some sexual assault survivors still feel silenced

By Andrea Johnson

Nov. 26, 2018

You might have seen the words appear in your Twitter feed for the first time last fall and wondered what it meant. #MeToo. Maybe it was posted with a news article or on a verified account, or maybe it came from your friend’s personal account. Either way, that probably wasn’t the last time you saw or heard those words.

The hashtag signified a refusal to dismiss sexual assault and harassment. It empowered survivors to speak up and say what they had never said before: “It happened to me too.” Some praised the survivors who called out their abusers, but others expressed pity for the accused. Some think the #MeToo Movement has ushered in a dangerous time for men because women can harm a man’s reputation, cost him his job or his freedom with their condemning words. A new hashtag, #HimToo, emerged in support of those accused men when U.S. Supreme Court nominee – now a confirmed justice – Brett Kavanaugh defended himself against Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations.

If a supposedly reputable man like Kavanaugh or an esteemed Hollywood king like Weinstein can be pulled down off their pedestals with a “me too” declaration, then no man is safe, critics say. But let’s get real: No one is safe from anything. We’re all potential victims, and we’re all potential perpetrators. It’s a matter of power, respect and dangerous misconceptions.

ORIGINS

The #MeToo movement picked up last fall in the wake of the Weinstein allegations when actress Alyssa Milano tweeted, “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.” Responses flooded in, now totaling at least 66,000 replies. But the movement actually began before the hashtag in 2006 with Tarana Burke, a youth worker who wanted to help survivors of sexual violence, particularly women of color. She sought to address the scarcity of resources and form a community of advocates.

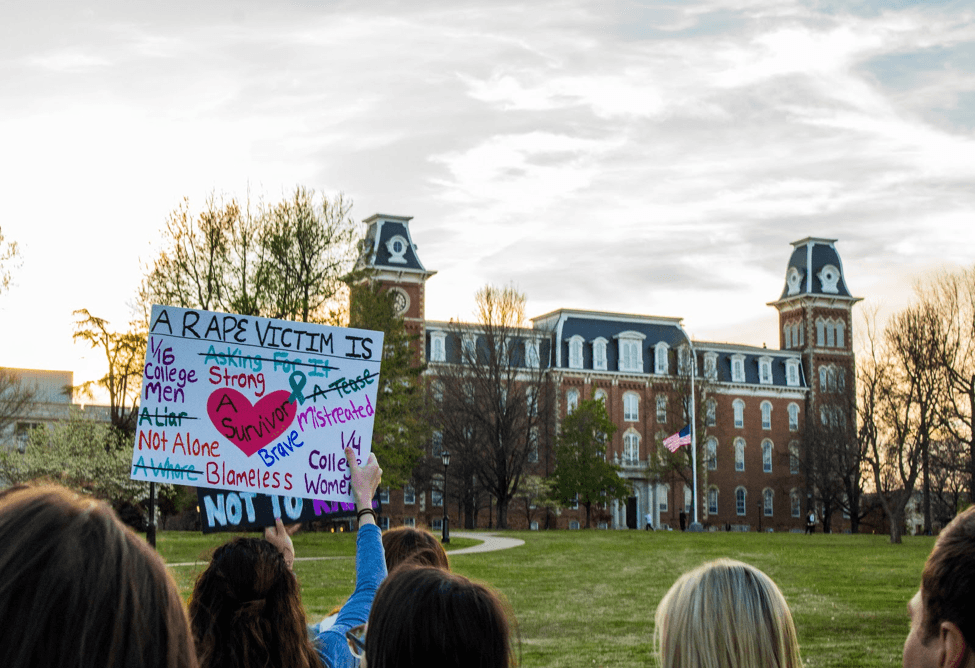

When the hashtag erupted, it launched an unprecedented national conversation about the problem. Since fall 2017, we’ve seen men and women take to the streets in protest, speaking out against sexual crimes and demanding respect for their bodies. Northwest Arkansas locals led Fayetteville’s first #MeToo March on April 21, and approximately 75 people joined in support.

That same month our University of Arkansas student newspaper, The Arkansas Traveler, organized a special issue dedicated to sexual assault prevention on campus. University officials deemed the coverage accurate and upsetting but necessary to see.

After publishing that issue, I was told it needed a more diverse set of narratives, and as an editor on the project, I agreed. However, we were limited to telling the stories of a few women who agreed to work with us.

The bravery some survivors feel as a result of #MeToo doesn’t translate to every survivor, said Anne Shelley, executive director of the NWA Center for Sexual Assault in Springdale.

“We do see more awareness as far as the community, but when that person is coming to us who has just been raped, they’re not thinking about the #MeToo,” Shelley said. “They’re not feeling like ‘The whole world is behind me.’ They’re feeling the same thing most survivors feel, which is ‘I’m completely alone.’”

Photo by Andrea Johnson / Illustration by Raleigh Anderson

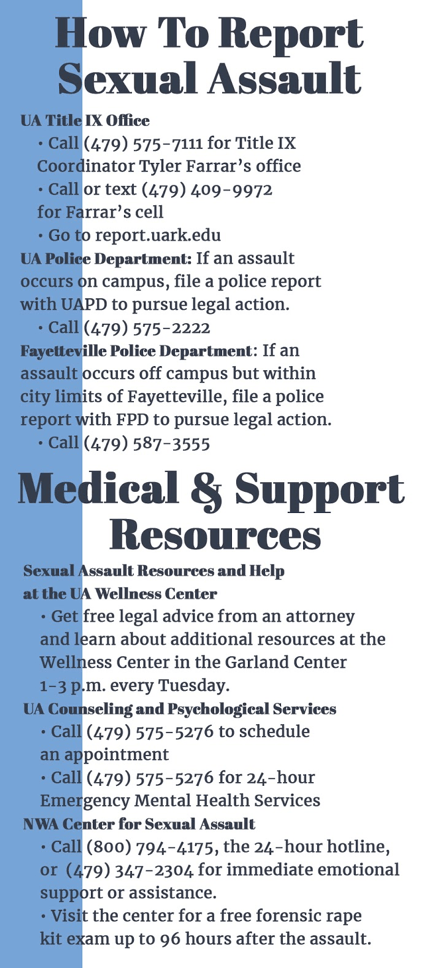

Survivors are often unsure of where to go for support, Shelley said, so the center aims to provide a place of refuge and guidance. Staff help people compile a rape kit, walk through a medical exam and get counseling among other services. And because sexual assault affects all types of people, the center employs advocates who represent minority communities.

“We see trans women, and gay men, and straight men, and undocumented people who do not speak English, and elderly women with Alzheimer’s, and the male clients who were assaulted as children,” Shelley said.

Olivia Whitley, an advocate at the center for black survivors, thinks diversity among staff helps survivors find someone they relate to in some way, she said.

“Seeing someone that you can identify with in some aspect is a comfort in traumatic experiences,” Whitley said.

Jennifer Arana, the center’s bilingual advocate, has seen survivors who are undocumented immigrants find some relief in knowing the center will not report them to immigration authorities, she said.

“When you come in here, it does not have to be reported to the police department. That’s your decision,” Arana said.

There are so many stories to tell, and journalists might never uncover them all, but this series is an attempt to broaden your understanding of a complex problem. And if you have a story you want to tell, I speak on behalf of University of Arkansas student media in saying we want to hear it. Help us educate our campus and community.

University of Arkansas students and faculty walk in the annual Take Back The Night march April 19. Photo by Jake Halbert, courtesy of The Arkansas Traveler

‘YES MEANS YES’

UA Clinical Assistant Professor Christopher Shields, who holds a Juris Doctorate law degree, has taught criminal law at the University of Arkansas for 11 years, and each semester he reviews sex crimes in his class. He dreads the discussion but would never avoid it. It’s too important, and he makes sure his students know that. Shields has also spoken to campus fraternities about consensual sexual activity and how it’s much more than the absence of “no.”

“We all say ‘no means no.’ I think that’s the wrong attitude,” Shields said. “I think yes means yes. That’s completely different.”

The UA Title IX Policy defines consent as a “clear, knowing and voluntary decision to engage in sexual activity.” It doesn’t count if a person consents by result of force, coercion, threat or intimidation. Consent is active, not passive, meaning mere silence should not be interpreted as consent.

According to Arkansas law, a person may commit sexual assault or rape if the victim was incapable of consenting to sexual activity. Incapability can stem from being physically helpless, meaning the victim was unconscious, unaware or otherwise physically unable to give consent. A victim could also be incapable of consent if they were under the influence of drugs or alcohol, or the victim has a mental illness or defect that affects their ability to knowingly consent.

A person may consent using nonverbal cues, but affirmative verbal cues are best to avoid miscommunication, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network. And consent for one activity at a certain time does not give consent for increased sexual activity or for recurring sexual activity.

During the #MeToo March in Fayetteville, Arkansas, a participant holds a sign April 21, condemning sexual assault. Photo by Kevin Snyder, courtesy of The Arkansas Traveler

Some students have confided in Shields by telling him about their own sexual assault experiences. For about nine years, only women came forward to him. In recent years, he’s talked to men who were victims of sexual assault too.

Shields thinks men are more hesitant to come forward because of the increased shame they experience. “The few who do talk about it are mocked,” he said. “It challenges their identity. It’s something that isn’t supposed to happen to men.”

Nine out of 10 rape victims are women, according to RAINN. People forget that women can assault men, and men can assault other men, Shields said. A male sexual assault survivor I spoke with agreed that people are less likely to acknowledge a man’s story. He shared his story with me on condition of anonymity, so I will use the pseudonym Jonathan.

It happened to him about 10 years ago while he was a college student at Missouri State University in Springfield. A friend drove Jonathan, tipsy but not incoherent, back to his dorm after a party. Jonathan felt tired and just wanted to crawl into his bed and sleep, he said. His roommate was awake.

“One of my friends at the party said ‘Oh you should go back and do something with your roommate,’ and I might have come back and made a joke with him,” Jonathan remembers.

His roommate was gay, and he knew Jonathan was gay. They were friends who met on Facebook and agreed to live together Jonathan’s sophomore year.

“I thought it was well understood that the joke I made by no means meant that I was interested in being sexually active with him,” Jonathan said. “The more I look back on it, I feel like he might have taken it more seriously.”

He remembers it like a dream: His roommate slipped into his bed, but Jonathan wasn’t fully aware of what he was doing or why he was on top of him. Jonathan woke up the next morning and discovered his underwear on backwards or inside out. He doesn’t remember exactly, but he realized that his memories weren’t from a bad dream. Physical clues led him to conclude he had been anally assaulted. Raped.

“I don’t think I initially labeled it sexual assault,” Jonathan said. Maybe it was an intoxicated misunderstanding – the result of a bad joke, he reasoned. The friends he told afterward brushed it off, laughing at the situation like someone might laugh when reminiscing on a moment of drunken karaoke.

“I kind of laughed it off with them like ‘Oh, maybe that wasn’t a big deal. Maybe this happens all the time to people,’” he said.

But then it happened again. It didn’t feel like a misunderstanding anymore. He thought about reporting it, but multiple reasons deterred him, such as his sexuality and underage drinking. He feared that at that time, in the fall of 2008, authorities might make a spectacle out of such an incident between two young gay men, he said.

“I was afraid of retaliation,” Jonathan said. “I was afraid I was going to be retaliated against by my rapist because he had a lot of friends there at school, and I felt like my life would’ve been hell if I would’ve gone and done something like that.”

Jonathan, who now lives in Northwest Arkansas, wishes he knew about resources like the NWA Center for Sexual Assault in his college town, he said. A month or two later he confided in his mother who didn’t dismiss the incident. She called it assault, and so did Jonathan. He knows that he never consented. He now knows it wasn’t his fault.

THE UGLY REALITY

“I think the myth is that it is the straight, pretty, young, white woman, but rape and sexual assault is not about beauty and attraction,” Shelley said, speaking from experiences at the NWA Center for Sexual Assault. “It’s about power and violence and control.”

Sexual violence isn’t a new problem. What’s new is the level of openness regarding such intimate crimes. More survivors are sharing their painful stories to raise awareness of the problem, hoping that what happens in the dark will not remain hidden – that people will hold each other accountable.

And it’s not just a problem among powerful public figures. The perpetrator could be your ex, your roommate, that guy you’ve been crushing on or that stranger on the bus. It’s a problem in families, in churches, among teenagers and college students and within workplaces everywhere.