How dementia affects those surrounding the diagnosed.

By Katie Serrano

April 4, 2019

“I love you,” I said in a wavering, barely-there voice as I held back tears, keeping them from falling down my face.

Through foggy, confused eyes I received an “I love you” back, although my grandma had no idea who she was talking to.

Me, my mother, father and sister had been sitting in the nursing home recreation room outside of Ann Arbor, Michigan in October of 2017 for a little less than an hour when we were finally able to get my grandma to speak to us.

“We love you, Bumba.” That phrase was the only combination of words that passed through the sturdy wall that had been built up around my grandma’s mind that blocked almost all of her memories. She could only understand words of love from her grandchildren and the nickname we had given her from the time we were children.

Me, my sister and father hadn’t seen my grandma in four years. The guilt of not seeing her enough, the reality that she didn’t even know who her own daughter or grandchildren sitting right in front of her were, and the realization that this could be my own mother someday was all too much for me.

I had to leave the room.

…

The diagnosis of dementia seems so far detached from a 21-year-old college student, but when I think about how my 84-year-old grandma Lillian McLeod has fallen victim to it, and my grandma’s mom before that, and that both me or my mom may become a victim one day, it becomes a pretty present fear.

Approximately 50 million people have dementia worldwide, and there are nearly 10 million new cases every year. The total number of people with dementia is projected to reach 82 million in 2030 and 152 in 2050, according to the World Health Organization.

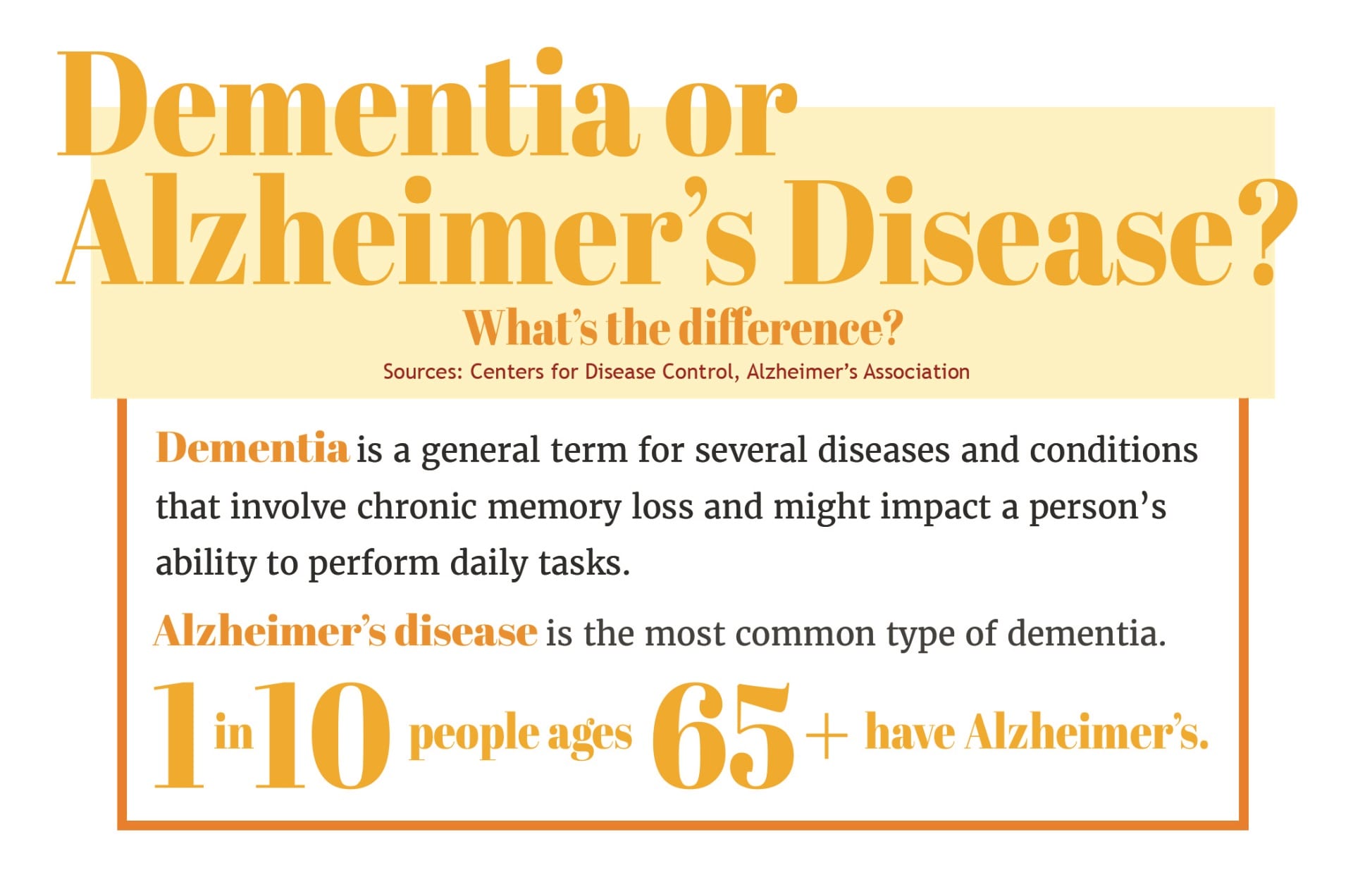

Graphic by Sarah Young

When my mother fumbles around her purse, searching for her keys that she had in her hand less than a minute ago, it may seem like any other forgetful bout that anyone can experience day to day. But then, when a few hours later she puts her phone in her purse, and not five minutes later forgets where it is once it starts ringing, the implications of these small, forgetful moments carry a significant weight in my mind. Because when four generations of women in your family have succumbed to dementia’s unrelenting, unforgiving genetic mutation that steals your memories, these forgetful moments seem to be foreshadowing something much more serious.

The total number of people with dementia is projected to reach 82 million in 2030 and 152 million in 2050, according to the World Health Organization. But it reaches exponentially more people than the statistic shows. Dementia affects the daughter who has to decide when to put her mother in a nursing home, the son who has to get another job to pay for the nursing home, the in-law whose marriage takes a toll from the stress of it all, and the grandchildren who witness everything.

…

When my family moved from Michigan to Texas in 2005 because of my father’s job, my grandma was still in good health. It was hard for my mother to leave all of her relatives, but there was no animosity between them.

I have fond memories of my grandma flying to Texas to come visit us in the summer, swimming in our pool or playing foosball with us. If she didn’t come to us, we would make the 24-hour drive up to Michigan at least twice a year with our family for the first few years after moving. I didn’t think much of it when our trips came to a sudden halt after the summer of 2009, assuming it was because of our increasingly busy schedules as we got older.

I never thought it was because my mother and uncle had severed ties. They couldn’t agree what to do with my grandma and her increasingly forgetful mind. My sister and I, who were around 12 and 15 years old at the time, didn’t quite understand that over the course of those four years my grandma was not only forgetting small, everyday things like where she put her keys. She was forgetting how to drive completely, would wet herself or hadn’t paid her bills in months and thought nothing of it.

“There may have been signs of symptoms those first few years after we left that I either missed or chose to ignore,” my mother Toni Serrano said. “Of course I have guilt about not being there when the syndrome really began to start showing itself, but nothing was going to stop it.”

Dementia affects memory, thinking and social abilities severely enough to interfere with daily functioning, according to the Mayo Clinic. Notable symptoms, other than memory loss, include difficulty communicating, planning, organizing and reasoning, as well as confusion and disorientation. Psychological changes might include personality changes, depression or hallucinations.

When it came to my grandma, she experienced all of these changes. She had always been the sweetest woman in the room, but her dementia – her confusion and frustration – caused her to be outright mean to the ones she loved. She would hallucinate people from the television screen, thinking that they were sitting next to her having a conversation. She would make up imaginary men and children in her head, promising us they were real when nobody had any idea what she was talking about.

A parental history of dementia increases the risk of dementia, especially if they are diagnosed before the age of 80, according to a study by The American Academy of Neurology. Other factors such as smoking or lack of a healthy diet can contribute to symptoms as well, but having a family history of dementia puts you at greater risk of developing the condition, according to the Mayo Clinic.

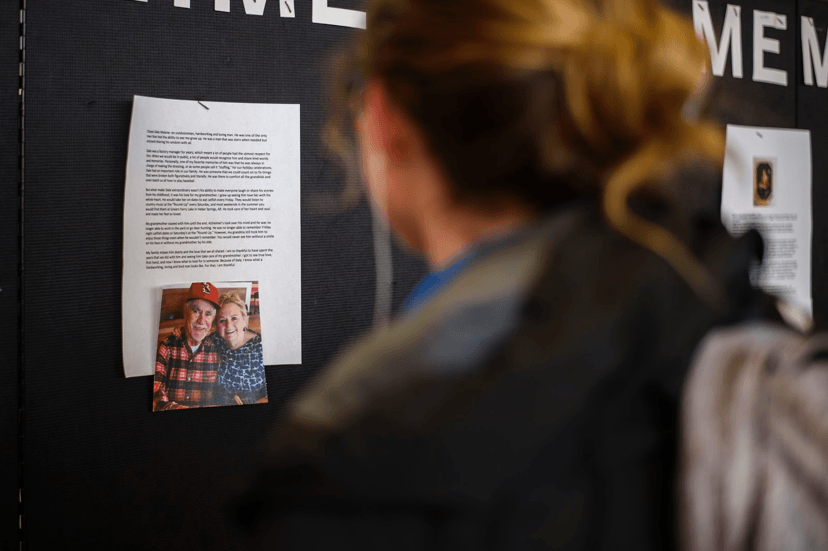

Junior Trinity Kenny reads one of the testimonials posted on the Alzheimer Memorial Wall in the Arkansas Union Connections Lounge on Feb. 25. Photos by Kevin Snyder

Dementia affects over 35 million families worldwide who must make decisions about everyday care, medical treatment and long-term care arrangements. The decisions cause complex family, ethical and legal dilemmas and hinge on the fact that the decisions don’t involve the person with dementia making the decisions about their own care, according to an article from the International Journal of Social Research and Practice.

…

In the summer of 2009, my family took our regular trip to Michigan for the summer, staying at my grandma’s house like we always did.

But when we walked in the door, I noticed the abnormal amount of dirt that had built up in her usually clean green carpet. I was able to run my finger along the blinds next to her La-Z-Boy recliner and see the cloud of dust that slowly showered off of it. I was confused by the chair sitting in her shower and the absurd amount of frozen meals in her fridge.

My sister’s first memory of the severity of the situation was that same summer in 2009.

“Our grandma woke up in the middle of the night, visibly confused and disoriented, saying she had to go to work even though she was hundreds of miles away from her hometown, and she was retired,” my sister Alex Serrano said. “It was then that I knew that dementia may be creeping in. I just didn’t know that it would creep in so fast.”

Lillian McLeod poses for a portrait taken at her church in 2004. Photo courtesy of Katie Serrano

My sister and I visit our grandma, Lillian McLeod, in her nursing home in October 2017. Photo courtesy of Katie Serrano

My mom didn’t understand how my grandma’s mind had changed so quickly in the year that she hadn’t seen her.

“That’s the first time that I saw my mom and she wasn’t the same woman that I’ve known my entire life,” Toni said through tears. “And that’s when things between me and my brother started to go south.”

She said that the first thing she felt was anger, specifically toward her brother, who hadn’t told her what was happening.

“This was all very detrimental to my brother and I’s relationship,” my mom said. “We disagreed about her care, but since I didn’t live in Michigan, I didn’t feel like I had a right to say too much. I didn’t want her to be alone, but since she had no money because of years and years of bad decisions, her resources were limited.”

Dementia can have difficult effects on family members who care for those living with dementia. Trying to balance the normal activities of family, career and personal time, caregivers also devote themselves to round-the-clock care and support of their loved ones. For any normal human being, the increasing level of commitment required can be burdensome, exhausting and even dangerous, said Amanda King, executive director at Clarity Pointe Assisted Living Center in Jacksonville, Florida.

“For these reasons, it is vitally important for families to understand the potential risks and consequences in advance and take steps to prepare for them,” King said. “The sooner you organize your resources and develop a plan for care, the less stressful and draining your life will be.”

In the years following that summer, my mom and uncle spent hours on the phone arguing, yelling, trying to come to some sort of agreement on what to do with her. As these phone calls became more and more frequent between 2007-2009, the animosity and resentment my uncle had toward my mom over the fact that she was across the country only grew stronger.

“Hearing your wife on the phone with her brother in the middle of the night crying, arguing about what to do with their mom and feeling helpless – it makes you ask yourself, ‘What is God’s plan in all of this? Why hasn’t he just taken her (my grandma) home to heaven yet?’” my dad, Ernie Serrano said.

…

For as long as I can remember, we called my grandma “Bumba” because my oldest cousin couldn’t say the word grandma.

Our “Bumba” was the most generous, goofy and kind-hearted grandma who was obsessed with game shows and collected way too many elephant figurines that she lined up along her TV stand, in her China cabinet and on her end tables.

When I think back to my childhood, I have the fondest memories sitting on her pale green carpet, watching “Family Feud” as she sat in her recliner behind me, answering along to Richard Karn, John O’Hurley and Steve Harvey as the years went on.

I didn’t know much about dementia as a 10, 11 and 12-year-old, but I began to see a shift in the grandma, the Bumba, who we all knew when the dementia started taking a hold.

“I think Steve Harvey is my favorite host,” I remember stating to my grandma one afternoon during one of our Michigan visits. I rocked in her recliner while she sat on the couch to my right.

“Who?” she asked me, confused, as if I had just woken her up from sleep and shouted the question in her face.

I remember laughing, thinking she was making a joke. How could she not know the name of man that she sees on her television screen every evening at 5?

I didn’t realize at the time that not even five years later she wouldn’t remember how to turn a TV on by herself.

…

My grandma ended up moving in with my uncle in 2015, about seven years after the first signs of her syndrome began showing.

“My brother and sister-in-law resented me for many years,” my mom said. “Our relationship is better now, but it took a toll on all of us. I will be forever grateful to my brother and sister-in-law for taking her in to their home for as long as they did.”

After a year or so of my grandma living with my aunt and uncle, she was moved from nursing home to nursing home, trying to find one that my family could afford. She finally settled into a group home, where she lived with five other women with dementia.

“She was very unhappy and angry there,” my mom said. “My brother would call me, telling me that she refused to eat this day, or would lash out, yell or attempt to hit her caretakers another day.”

In 2017 she was moved to the nursing home where she is currently living, and although my grandma isn’t significantly suffering physically, my mom said she has wondered whether things would be different if they hadn’t waited so long to put her in a stable environment instead of moving her around so much.

“She has good days and bad days,” my mom said. “But good days are relative. She doesn’t know anyone anymore, but she still enjoys candy and ice cream, although she needs help eating them.”

In 2015, when my grandma was still living with my uncle, my mom went to Michigan and they all had a sleepover. They took selfies on an iPad and she laughed.

“That is the last time I remember her really smiling,” my mom said.

…

Around 1988, when my mom was 31 and my grandma was 55, my grandma had to put my great-grandmother in a nursing home.

My own mom was hesitant to put my grandma in a nursing home because she saw the effects it had on my great-grandmother when she was younger. My mom was also concerned about transfer trauma.

Transfer trauma is a term used to describe the stress that a person with dementia may experience when changing living environments, according to the Crisis Prevention Institute. Transfer trauma is more commonly seen in a person in the early stages of dementia and when they are moved from their home into a facility.

The move from the home that my grandma had known for over 20 years, to my uncle’s house, to a group home and then to a nursing home caused her severe confusion and frustration. She could never settle into a set routine and for years asked when she would get to go back to her home.

Just as my grandma struggled with putting her mom in a nursing home, and just as my mom has struggled with putting her mother in one, me and my sister already grapple with the thought as well.

My mother and I pose for a photo on Mother’s Day in 2017. Photo courtesy of Katie Serrano

“I, of course, have fears that dementia will affect others in our family in the future, and at this point, I don’t even want to think about what we will have to do with our mother,” my sister said. “But I’m also optimistic. Science and medicine continue to make breakthroughs day after day, and I’m hopeful that there will be a cure for Alzheimer’s and dementia … sooner rather than later.”

…

As I was pacing the hallway outside that rec-room in 2017, letting the tears openly fall down my face, my mom came to find me. Those who know me know I don’t cry very easily or often, and I definitely try not to show that side of me to many people, even to my own family. So when my mom saw the state I was in, she did what any other mom would do. She embraced and comforted me until I was able to speak again.

“I just don’t know what I’m going to do if this ever happens to you,” I attempted to say through a wretched sob, feeling guilty that I was the one needing to be comforted in this situation when everyone else in my family, who have been through so much more, was being so strong.

“You know that I don’t want this for you,” my mom said. “I don’t want you to suffer like I’ve had to. Don’t feel guilty for whatever you end up having to do, okay?” she said in such a sure and strong voice.

Art by Ally Gibbons

I don’t want to think about that situation, but I know my mom has a plan in a series of letters that she has written to me, my sister and my father that she plans to give us if the time ever comes.

I don’t know how she has found so much peace in this situation, and I may never understand it. I can only hope to have the strength that she does to get through it.

“I know it might seem hopeless at times, and it’s hard to understand or make sense of all this,” my mom has said. “My husband has been amazing through all of this, and has always been supportive to me and kind to my mom. He’s gone above and beyond to help with this situation. But I also know that when this is all over, she’ll be back with my dad in heaven, and sometimes I’m able to smile about that. Wherever her mind is at right now, I know it will find its way back to him.”

My sister and I are proud of the way our mom carries herself, even in the midst of all this fear.

My mom and I walked back to the rec-room, arm in arm, and sat back down with my grandma. Although my grandma’s eyes were still foggy, a smile broke across her face as she repeated back to all of us, “I love you.”